Suffering during the Lockdown

Freiburg, Jun 26, 2020

Social isolation, restrictions to personal freedom, economic worries, the double burden of working and having to take care of children, fears of losing one’s job, worries about society falling apart, not to mention a new kind of virus that can be life threatening: For the past few months, the coronavirus has put this country in a state of emergency. Recently, the effects this is having on mental health has been gaining attention. But what exactly are people concerned about, and does this have to do with the containment measures taken by the state they live in, for example? The economists Dr. Stephanie Armbruster and her colleague Valentin Klotzbücher, both from the University of Freiburg, have researched effects like this in their new study in which they relied on a large set of data from the crisis hotline Telefonseelsorge, which is active all over Germany.

During the first few weeks of the shutdown, a growing number of people called the Telefonseelsorge crisis hotline to get help coping with worry and distress. Photo: Alex from the Rock/stock.adobe.com

During the first few weeks of the shutdown, a growing number of people called the Telefonseelsorge crisis hotline to get help coping with worry and distress. Photo: Alex from the Rock/stock.adobe.com

When the quarantine in Wuhan was lifted, reports began to circulate about couples getting divorced and splitting up. This seemed plausible: Living together in close quarters for an indefinite amount of time, being cut off from other social contacts, and not having the usual daily routine can all carry a lot of conflict potential. Then, there was also the experience of the SARS epidemic from 2003 to draw on, when the suicide rate increased significantly in China. The warning signs were there for Europe to read, but at the beginning of 2020, Europe was still just watching the Covid-19 pandemic from afar.

It was not until society shut down, when Germany learned new rules of social behavior and businesses closed in the middle of March, when people were learning how to deal with the lockdown with varying degrees of success that issues of mental health and quality of life became prominent here as well. Not only the coronavirus, the Covid-19 illness it causes, and the economic consequences of the shutdown, but also mental health increasingly became a focus in the media, which often called on a scientific expert to provide advice. For example, on March 25, the public radio station Deutschlandfunk warned about the psychological consequences of the pandemic and suggested “strategies for coping with fear and loneliness.” Also, people with depression and anxiety disorders talked about how they were dealing with the crises on “Spiegel online” under the headline “It feels as if all my achievements have been for nothing.”

Academic curiosity and relevance to society

Stephanie Armbruster and Valentin Klotzbücher were aware that a rise in mental health problems made sense, yet something did not feel quite right to them. They asked themselves, “Wouldn’t it possible to quantify this, instead of just claiming it?” The two researchers from the University of Freiburg are economists. Armbruster, who just earned her PhD, works at the Institute of Environmental Economics and Resource Management at the University of Freiburg and is also a research assistant at the University of Basel. Klotzbücher is currently writing his PhD thesis at the University of Freiburg’s Wilfried Guth Endowed Chair for Constitutional Political Economy and Competition Policy. The two share an academic curiosity paired with the satisfaction of researching a topic that is relevant to society. “If you work with data, you also have to work with the coronavirus. The whole situation is like a huge experiment,” says Armbruster.

That a scientific journal published their study “Lost in Lockdown? Covid-19, Social-Distancing, and Mental Health in Germany” already at the end of April was a success in the authors’ eyes: Academic papers dealing with this burning issue are currently reaching publication faster than normal. Armbruster and Klotzbücher’s study is based on data from the Telefonseelsorge crisis hotline in Germany. Originally, they wanted to use data from Google Trends, which shows current search requests, but then, in the process of their research, they googled “mental health problems” and like everyone else, they found the crisis hotline.

The hotline of the Telefonseelsorge, with 107 offices all over Germany, is run by more than 7,500 volunteers and 300-plus employees, all of whom save valuable caller data for each call, chat, or email. Information includes the subject of the call; the caller’s assumed age, gender, housing situation, and living conditions; and the nature of their employment. These data are then anonymized and managed using a central statistics software. Armbruster and Klotzbücher relied on data from 2020 for their study, while also drawing on data from 2019 for comparison.

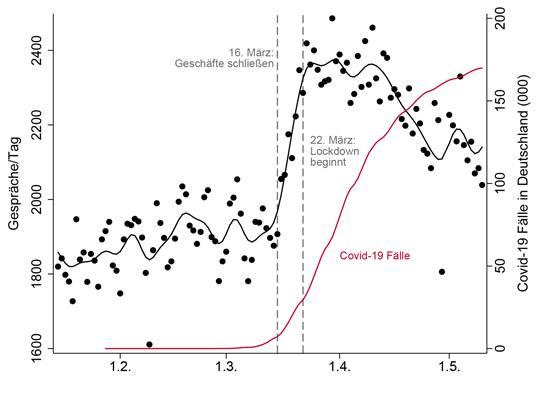

A diagram from the study shows that, as containment measures and the number of Covid-19 infections increased, so did the number of calls to the crisis hotline. Source: Stephanie Armbruster, Valentin Klotzbücher

A diagram from the study shows that, as containment measures and the number of Covid-19 infections increased, so did the number of calls to the crisis hotline. Source: Stephanie Armbruster, Valentin Klotzbücher

Loneliness, anxiety, and depression

Based on this large data set, Armbruster and Klotzbücher were able to identify certain criteria, such as mental health, physical and sexual violence, and social and economic problems. They were also able to link the data with the virus containment measures, which varied in strictness from state to state in Germany, the rate of infection and mortality, and the unemployment rate. In their paper, they explained that the need to talk to someone rose by 20 percent during the first week of the lockdown, and that it decreased gradually in the third week. The jump was primarily due to mental problems like loneliness, anxiety, and depression.

The increase was more pronounced in states where measures were stricter. While anxiety was a problem already four weeks prior to the lockdown, loneliness became the leading issue in the first week of social distancing. Fittingly, people who live alone were more likely to call. Economic worries, on the other hand, played only a minor role at this time. Another major issue was domestic violence, as could be seen by the rise in the number of calls regarding this issue, despite the fact that there is a hotline devoted entirely to domestic abuse and the fact that it had to be assumed the aggressor was in the same household at the time of the call.

What the data reveal

So why did the two economists choose this moment to study mental health during the pandemic? “We do statistics. And if economists find data they can use to research something relevant, they jump at the chance,” says Klotzbücher. However, he also admitted, “We are not experts in psychology.” To this, Armbruster added, “The subject of our research is not that far removed from what economists do in principle, which is to research how political measures affect the population and what benefits they might have.”

With this in mind, one wonders if it would not be interesting to determine the advantages and disadvantages of containment measures and to make suggestions for a possible second wave. “That would be ambitious,” they say. Klotzbücher explains that this is because the value of preventing an infection cannot be determined if you don’t know the damage it would have caused. The same is true when trying to measure the cost of the shutdown in terms of how it has likely made it (much) more difficult for many high school graduates to get a foothold in the job market. While it may be true that the hotline callers represent only a small sample of the entire population, the two economists agree that services like the Telefonseelsorge crisis hotline do help, and that they could become even more important in the future if there is a second wave. In the meantime, Stephanie Armbruster and Valentin Klotzbücher will continue to watch the situation closely as they pursue their plans of creating a network with Swiss colleagues to collect data from around the world.

Annette Hoffmann

Study by Stephanie Armbruster and Valentin Klotzbücher