Attack on the blind spot

Freiburg, Jul 17, 2018

For many years the police sought an “unnamed female person” whose DNA was found at several crime scenes - including the police car driven by policewoman Michèle Kiesewetter, who was shot dead in Heilbronn in 2007. Today we know that the murder was carried out by an extremist right-wing group known as the National Socialist Underground or NSU. But the investigators suspected the unknown woman to be a member of the Sinti and Roma minority. The hunt for the “Heilbronn phantom” was on. The police and the media placed an entire minority group under suspicion, says Professor Anna Lipphardt. She is a University of Freiburg cultural anthropologist researching the case, reconstructing the investigation procedures. She spoke to Rimma Gerenstein about where mistakes were made, how the media played a role in discrimination, and how to combat institutional racism.

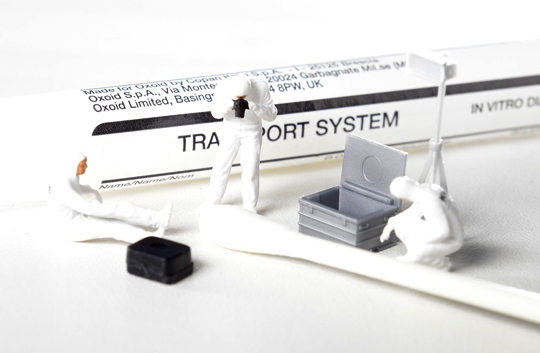

Extended DNA testing was used in the case of the “Heilbronn phantom.” As the method is not permitted in Germany, investigators got help from Austria. Photo: Gerhard Seybert/Fotolia

Professor Lipphardt, there are conflicting opinions on the recent judgement in the NSU trial; some are happy that the trial is over, while others fear that it will mark the end of investigations. How do you see the decision?

Anna Lipphardt: I have conflicting feelings, as many people do who have followed the trial closely. On the one hand I am relieved that it is finally over and so is the smear campaign conducted by the defence. On the other hand I never had any illusions that there would be a full and comprehensive explanation of the events.

Why is that?

Federal prosecutors drew up narrowly-defined charges, and it became clear very quickly that the trial would exclude central aspects - for instance the question of how far the NSU network reached and what support it had in the local right-wing scene. Nor did the trial seek to systematically clarify the responsibility of the authorities or the direct involvement of a government agent, as in the case of the secret police officer Andreas Temme, who was present during the murder of the Kassel internet café owner Halit Yozgat. It also became clear quite early that the court would not look at the issue of the investigations which were largely based on prejudice against certain groups, nor at the structurally embedded racism among police and legal structures. Many were expecting that the court would make a critical analysis of this - even if a criminal procedure cannot make a comprehensive job of it.

One prominent example is the case of the “Heilbronn phantom.” Where do you see that the investigators allowed themselves to be guided by prejudice?

The federal parliamentary inquiry came to the conclusion that discrimination was a starting point in the investigation. My research reinforces this assumption and reveals that the discrimination ran right through all the stages of the case - from the on-the-spot investigators, to the operative case analysis, to the communications with forensics. Look at how the police arrived at the theory that the female perpetrator must be a Romni: A trace of female DNA was found on the police car - DNA which was found at countless crime scenes in Germany and Austria - as well as here in Freiburg. In Heilbronn they concluded that the perpetrator must be a highly mobile and dangerous person. The investigators in Heilbronn called in detectives from Austria and had them conduct an investigation into the bio-geographical origins of the woman suspected of the crime. That is a highly complex genetic procedure which is easily subject to error, and which was not allowed in Germany and still isn’t. The report found that the person was likely to have originated from the Russian Federation or neighboring areas. The investigators in Heilbronn interpreted that to mean, “that fits our theory that it must be a woman from a Roma family.” They translated a geographical estimation into an ethnic category. “The trail leads to the gypsy community” was the quote by the head of the investigation, cited in Stern magazine.

So the media brought the discrimination into the public forum?

The police and the media together created the “Heilbronn phantom” and kept reinforcing its power. It was part of the strategy, that the investigators worked closely with the press and spoke openly with the reporters. The aim was to motivate the public to come forward with eyewitness accounts. Several reporters accompanied the police work for weeks as if they were war correspondents. Eventually it was found that the source of the female DNA was contamination in the factory where swabs used for collecting evidence were made; the media were left red-faced at having uncritically reported what the police told them, in some cases even dramatizing it. All the journalists I’ve talked to admitted that they found the story “incredibly exciting.” “It was a really sexy story,” one of them said. The result was that a whole minority was placed under suspicion.

If there had been good reason to believe that the culprit came from Heilbronn, perhaps blond men with blue eyes would have been a police target. Put another way - isn’t every profiling discrimination in some way?

The decisive question is when and why did the police start putting aside all the other indicators - and there were certainly hints pointing towards the right-wing scene and local organized crime - and only following one single lead. I read the investigation files. It is shocking to see what discriminatory categories were used.

Can you give an example?

The official file is a good example. It lists all the witnesses. There is a category of “witnesses A to M” and “witnesses N to Z.” And then there is the category “travelers.” That is the only group for which a separate category was set up. Or the witness statements: For instance, a member of a Roma family was interrogated in Belgrade and connected up to a lie detector. The result was negative. The police psychologist’s report stated that the man questioned was “a typical example of his ethnic group,” so “a lie is an essential part of his socialisation.” That means: as a gypsy, the man has been used to lying since childhood and has learned to trick a polygraph.

“We are not talking about two or three officers who missed the police anti-discrimination classes”: Anna Lipphardt stresses that the case of the “Heilbronn phantom” was about institutionalized racism. Photo: Harald Neumann

Isn’t it possible that this is about just one racist police officer who made the wrong decisions?

We are not talking about two or three officers who happened to have missed the police classes on anti-discrimination. This case makes clear how widely distributed group-related prejudices and institutional racism are. The operative case analysis by the State Office of Criminal Investigation in Stuttgart for instance used a profile of the unknown woman as police training material; it uses expressions like “scrounging, stealing, vagrancy, moving around, making a living by crime” to describe the “typical” lifestyle of Sinti and Roma. That is not old material from the 1940s. The concept of the “lifestyle” comes from Sociology and was developed in the 1990s.

You have talked a lot to investigators over the years.

Yes - and they often appear not to realize that they act discriminatively. When I raise the issue of the Heilbronn case and the visibly discriminative approaches to the investigation, the investigators usually feel that it is an attack on the institution of the police and enormous criticism of their personal view of their profession. After that, a constructive conversation is not usually possible. The officers who made witness statements in the Munich trial on the other murders and bombings carried out by the NSU - they too made it clear that they see no discrimination towards the families of the murder victims or the German Turkish community in their behavior during the investigation, and that they would do the same again.

How can we combat institutional racism?

I believe that the case of the “Heilbronn phantom” in Baden-Württemberg needs to be thoroughly investigated. Only an independent commission can do that, one which of course includes representatives of the police and justice authorities - but also representatives of the Central Council of Sinti and Roma, as well as critical criminologists and experts from the field of discrimination research. Police and the justice system cannot continue to just reject the criticism which came out over the course of the NSU trial; they need to finally take it constructively. Like all state institutions they are obliged to observe article 3 of Germany’s Basic Law: They have to ensure that they do not disadvantage anyone because of his or her background, religion, or political views. Furthermore, researchers, journalists and legal experts have to have clearly-defined access to the files, so that they can help with clarification. Up to now it has been an opaque procedure. If the files are not opened, the impression is given that the state and its institutions have something to hide - and the mistrust of the people will continue to grow. That can’t be in the interests of the Federal Republic of Germany nor of its police and justice system.