Staying Curious

Freiburg, Oct 22, 2018

It’s not every day that a wife and husband are named Honorary Senators of the University of Freiburg, like Gerda and Dr. Fritz Ruf in June 2018. Actually, this is the first time. The university distinguishes persons who have renders special services to the university by conferring on them the title of Honorary Senator. The Rufs founded the Fritz-Hüttinger-Stiftung (Fritz Hüttinger Foundation) in 2006, and through their foundation, they have been supporting their alma mater for quite some time already. One of their accomplishments is the establishment of the Fritz Hüttinger Chair of Microelectronics, which was not only the first professorship to be named after someone at the University of Freiburg, but also set the course for the development of the Faculty of Engineering.

Fritz and Gerda Ruf have many reasons to visit their old hometown of Freiburg, including their involvement in the company Trumpf Hüttinger, which was founded by Gerda Ruf’s father in 1922. Photo: Thomas Kunz

Once called “Figaro” – not because of his hair, but because he wore a white hairdresser’s coat –Fritz Ruf began studying chemistry at the University of Freiburg in the winter semester of 1946/47, when laboratory coats were a scarce commodity. At the time, there was also technically no Department of Chemistry either, because it had been destroyed in an Allied air raid in November 1944. During the war, Ruf, who was born in 1927 in Waldkirch and grew up in Freiburg, served in the German Navy and was taken captive by the British for a short period. During his service and captivity, he learned many practical skills, like welding and how to drive and repair a tractor. After the war, as a future academic who always had his feet on the ground, he was just what the country desperately needed for reconstruction.

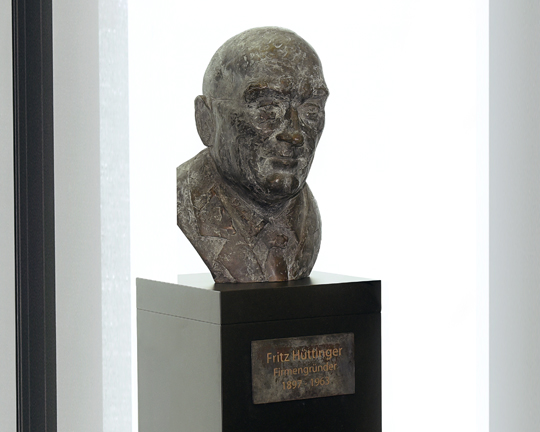

At the time, his future wife, Gerda Hüttinger, was also hard at work helping to rebuild Germany. Her father, Fritz Hüttinger, was the founder and owner of the Hüttinger factory (now Trumpf Hüttinger), which began manufacturing electronic medical devices in 1922. The factory had also been destroyed during the same November air raid in 1944, but it rose out of the ashes and gained a new foothold with an expanded production range. In 2013, the company changed its name from Hüttinger Elektronik to Trumpf Hüttinger. Not only did Gerda and Fritz Ruf start a long life together, but the name Hüttinger would also be closely tied to the University of Freiburg for a long time.

The Rufs donated a Hittite ritual platter made of clay to the Archaeological Collection of the University of Freiburg. Photo: Patrick Seeger

Looking Ahead

It all began with opera glasses. Gerda Hüttinger and Fritz Ruf met at the opera. She had a pair of opera glasses, and he didn’t, so she let him use hers. They were married in the Annakirche in Freiburg in 1957. Although they do have any children, they like to say that they’ve “adopted their own family” over the years. They celebrated their 60th wedding anniversary last year at the same place where they became engaged. Their love for culture has remained strong over the years. They remember the opera singer Fritz Wunderlich’s debut at the Freiburg Theater. Wunderlich had studied at the School of Music in Freiburg and went on to become a famous singer. They are also great fans of the renowned Freiburg Baroque Orchestra today. When the ensemble finally found a new home near the old trade fair building in town, this was also thanks to the Rufs. “We helped a little,” says Gerda Ruf modestly.

According to Gerda Ruf, it was natural that her husband did not go to work in her father’s company, where she herself was an employee for ten years. Fritz Ruf had decided that macromolecular chemistry was not for him, and he became fascinated with food chemistry instead, despite the fact that his professor at the time was Hermann Staudinger, who later received the Nobel Prize. Before he could begin his studies, however, the University first had to “invent” this new discipline. He thus became the first student in the program and went on to become a chemistry expert for the city’s health inspection office. “Whenever he walked in, people would run for cover,” his wife says, adding that she never understood the straightjacket mentality of her husband’s career as a civil servant. “Too regimented,” she says. However, Fritz Ruf was also making his own plans for the future at that time. He soon found a management position in the chemical industry, and the couple moved to Ludwigshafen, where Ruf focused on food additives – a career that would eventually take the Rufs to Karlsruhe and finally to Heilbronn, where they still live today.

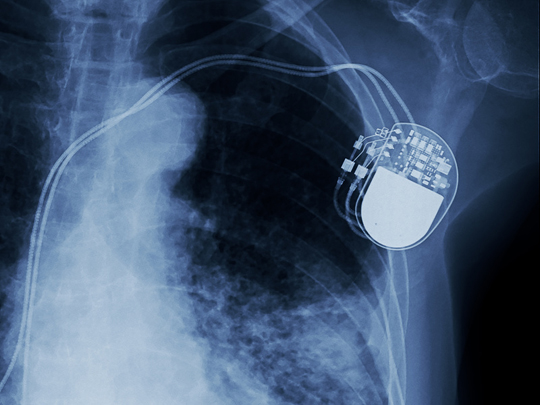

Through energy harvesting, a pacemaker can operate self-sufficiently by harvesting the power it needs from blood sugar in real time. Researchers with the Fritz Hüttinger Chair for Microelectronics are working on many groundbreaking methods like this. Photo: Choo/Fotolia

PhD at 65

“It was never boring,” says Gerda Ruf about their life together. Her husband admits that she not only enabled him to do what he wanted to do, “She was committed 100%.” On his lapel he wears a pin from the University of Freiburg, along with a Federal Cross of Merit, 1st Class (Bundesverdienstkreuz Erster Klasse), which was awarded to him by recommendation from the Federal Minister of Food and Agriculture. Fritz Ruf has not only made a name for himself in the fields of food legislation and nutritional science, he also earned a PhD when he was 65 and wrote his dissertation on the history of nutrition. His work on this subject sparked the couple’s interest in ancient artifacts related to food and drink. They have become great supporters of the University’s Archaeological Collection, and they recently donated a clay panel that is thousands of years old and bears an inscription about food rituals in Hittite cuneiform script. “This ritual panel is often regarded as a purity law and as the ‘oldest food law in the world,’” Fritz Ruf explains.

As Gerda Ruf puts it, “If you lose your curiosity, then sooner or later you’ll end up spending all your time in front of the TV or doing crossword puzzles.” That’s why she and her husband invested their own money in the Fritz-Hüttinger-Stiftung, which helps to cultivate curiosity and research at the University of Freiburg. They also like to keep up-to-date with what’s new in the world of research pursued by the chair they established – for example, energy harvesting. “We’re amazed at everything the students are developing,” Fritz Ruf says with pride. He is especially excited about the new technology that allows a pacemaker to use blood sugar to generate the power it needs in real time, especially since he himself once worked on dextrose products at the Maizena/Knorr corporation in Heilbronn.

Photo: Thomas Kunz

Gerda Ruf is the last shareholder from the Hüttinger family in the company her father once founded. Because her husband is also a member of the advisory board, both of them always have an excuse to come to Freiburg. One of their goals is to keep Fritz Hüttinger’s memory alive in the city, which is why they commissioned the sculpture Induktor, which was erected in front of the former Hüttinger factory on Elsässerstraße in 2017. A bust of the company’s founder is also installed in the new company building in the industrial area Auf der Haid. Standing next to the bust of his father-in-law, Fritz Ruf, who is now 91 years old, says, “I’m grateful for the life I’ve had.”

Anita Rüffer