Reading before Luther

Freiburg, May 22, 2017

A medieval studies course took advantage of the hype around the Luther Year 2017 and studied handwritten and printed German Bible translations – from before Luther’s time. What made the course unique is that all of the manuscripts analyzed in the course are held at the Freiburg University Library (UB). The centuries-old original documents are now part of an exhibition that will be on display at the adult education center Volkshochschule Freiburg until 23 June 2017.

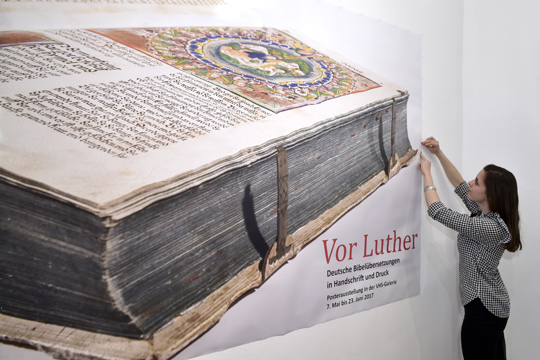

On display: The poster exhibition runs through 23 June 2017 at Volkshochschule Freiburg. Photo: Thomas Kunz

The triumph of the “people’s Bible,” published in full for the first time in 1534, would seem to be the work of Martin Luther alone. The famous reformer translated the Old Testament from the original Hebrew text and the New Testament from the Greek – that was something new. But what happened before Luther?

That is the question University of Freiburg students set out to answer under the guidance of the medievalist Dr. Balázs J. Nemes from the Department of German. In the course “Back to the Roots – Medieval German Literature from (Freiburg) Manuscripts,” they studied various forms of Bible translations that predate the famous reformer’s own translation with the aim of setting the record straight with regard to the popular image of Luther.

The Mentelin Bible, published in Strasbourg in 1466, just ten years after Gutenberg’s epoch-making printing of the Latin “Vulgate” Bible translation, was the first printed Bible in German. In fact, it was the first printed Bible in any European vernacular. “The subsequent decades up to 1518 saw 13 further editions of the German Bible, meaning the complete Bible, in the Upper German area alone,” explains Nemes. They were based on a translation from the 14th century, which for its part is just one of many (partial) translations of the Bible from the Middle Ages.

Fishing through a Current of Texts

Nemes and his master’s students selected models of various text types by fishing through a “broad current of texts,” as he calls it. In other words, they went back to the sources. And that is what made the course unique: These sources are all held in Freiburg. “I enjoy working with the holdings of the University Library,” says Nemes. “In 2006 the library acquired a former private collection from Berlin encompassing 30 manuscripts written in the vernacular that had not yet been fully analyzed and edited.”

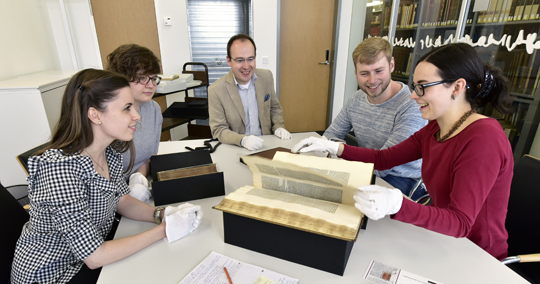

With special permission and white gloves: The team studies the valuable originals held at Freiburg University Library. Photo: Thomas Kunz

With special permission and white gloves: The team studies the valuable originals held at Freiburg University Library. Photo: Thomas Kunz

The participants of the seminar have now contributed to this goal. The six students and their teacher received special permission to study the more than 500-year-old documents with white gloves in the UB’s rare books and special collections reading room. Some of them are 30 by 40 centimeters large, weigh several kilograms, and are very bulky. Others measure only 8.5 by 11.5 centimeters, such as a leather-bound prayer book from the Late Middle Ages, which contains penitential psalms, is written on expensive parchment, and is richly illuminated with gold initials.

Valuable Snippets

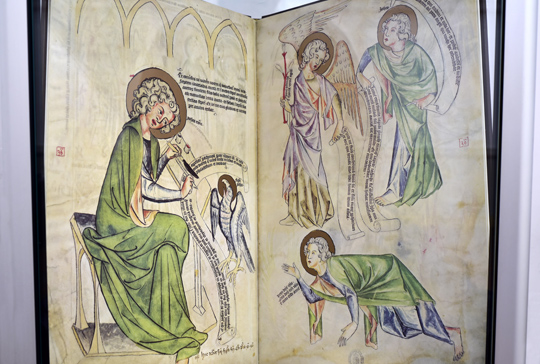

“The representative character of the manuscript points to the status of its owner, noblewoman. The content indicates that the owner had the prayer book made for her personal use,” explains course participant Chiara Mazzoleni. The manuscript Laura Hagen examined is completely different. It is a fragment of an apocalypse commentary penned by the knight Heinrich von Hesler. “The two tiny ‘snippets’ are folded and full of holes. They were probably used as folding material to stabilize the spine of a book or individual pages,” the student suspects.

John the Evangelist – Seer of the Apocalypse: The manuscript, probably written around 1350 in the Benedictine monastery in Erfurt, contains unusual illustrations reminiscent of the panel and wall painting of the time, including illustrations of the apocalypse. Photo: Thomas Kunz

Lea von Berg studied the picture Bible genre, a precursor of modern children’s Bibles, while Christoph Martin concentrated on pericopes – parts of the Bible read during church services. He was fascinated by the aura of the historic objects: “There are some things you can really only discover by examining the book itself rather than just its digitization. I also like the fact that our findings are not just being filed away somewhere but are being put on display in the exhibition.”

80 Pages and a Lot of Posters

The various types of medieval German Bible translations can be viewed on posters at the adult education center Volkshochschule Freiburg in the coming weeks. The exhibition also explores the transmission of printed Bible texts, which began in 1466, and shows the most important printed editions of the German Bible before Luther. This part of the exhibition was curated by the Freiburg medievalist Prof. Dr. Nikolaus Henkel.

It is a remarkable result for a seminar with six students: an exhibition and an 80-page “brochure,” as the team calls it with a touch of understatement. It is actually a small catalog the team put together and wrote texts for themselves.

The six master’s students prepared an exhibition and an 80-page catalog together with Balázs J. Nemes (left) and Nikolaus Henkel (right). Photo: Nasser Parvizi

Visit the Exhibition

The poster exhibition “Vor Luther – Deutsche Bibelübersetzungen in Handschrift und Druck” (“Before Luther – German Bible Translations in Manuscripts and Printed Books”) can be viewed until 23 June 2017 in the gallery of the Schwarzes Kloster at Volkshochschule Freiburg, Rotteckring 12, 79085 Freiburg. Opening hours are Monday through Thursday from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. and Friday from 9 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. Admission is free. Financial support for the exhibition was provided by student quality assurance funding from the “Innovative Studies 2017” project competition.

Alexander Ochs