Can do anything – but don’t have to

Freiburg, Apr 26, 2017

It’s not laziness, can’t be equated with free time, and it’s certainly not boredom: What, then, is “leisure”? At a Freiburg collaborative research center (SFB), academics from the fields of Philosophy, Literary Studies, Theology, Art History, Sociology, Psychology, and Cultural Anthropology worked on a cultural history of the phenomenon from 2013 to 2016. Rimma Gerenstein spoke with medievalist Rebekka Becker, English Studies specialist Pia Masurczak and psychologist Minh Tam Luong, all of whom completed their doctorates in this SFB.

Paradise of leisure: Tristan and Isolde live in their grotto, telling tales of yearning love; Isolde’s husband, King Marc, remains at court, disgruntled. Source: Wikimedia Commons

How did monks and nuns experience leisure? Did peasants, who worked in the fields all day, also have leisure time? How do works of literature from the Middle Ages to the 20th century present leisure? And what role does it play in today’s world, when the words “deceleration” and “mindfulness” appear in almost every self-help book? The SFB researchers have found one and the same pattern over the centuries. Leisure may last a minute or an hour and happen anywhere - at the beauty spa or at your desk or at a busy railroad station. It serves no purpose, neither recovery nor relaxation. Yet it may create a space which enable us to filter out the demands of everyday life for a moment and to become inspired. Yet leisure cannot be forced or held onto. And sometimes it is feared. After all, it could allow people to stop caring - to lose their ambitions and neglect their duties.

The temptation of indolence

The Middle High German poets Hartmann von Aue and Gottfried von Strassburg, were skeptical of such repose. They thought it was too close to indolence - even sin. Certainly, leisure is not to be expected in courtly novels. The Middle Ages remind us rather of the “ora et labora” maxim, or “arbeit umbe êre” (effort to obtain recognition) propagated by the legends of King Arthur around 1200. “It was chiefly the job of the knights to go out into the world and to fight. Nothing was allowed to hold them up on their quests,” says medievalist Rebekka Becker. Returning from their adventures bearing dented shields brought them recognition from the nobles at court. That was the ideal.

But knights could swiftly lose that recognition the moment they abdicated their responsibilities. This is reflected in the literature of the day, Becker explains. “Whenever the characters experience leisure it is always away from society. For instance, the knight Iwein loses his way and wanders through a garden of linden trees, springs, and birdsong - a place of freedom and latitude which can be seen as a contrast to the strict, representative culture at court.” But idle tarrying is followed by punishment. The “idlers” are held in contempt, and they are talked about behind their backs - and their guilty consciences torment them. When the prince, Erec, withdraws for weeks with his wife Enite to indulge in lovemaking, his subjects become restless, and the happiness at court threatens to disappear. Negatively and sometimes with an ironic undertone, the narrator comments on what happens when you never get out of bed.

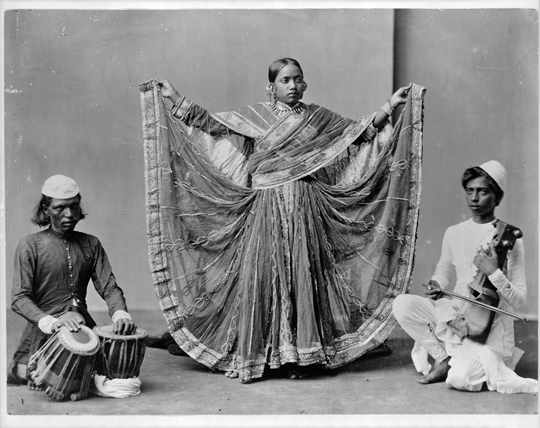

The nautch girls danced traditional Indian dances. For many British employees of the East India Company working there, these performances were a sought-after amusement at which they could experience leisure time. Photo: Library of Congress/LC-USZ62-35125

Becker stresses the inconsistency in the novels. “When the ruler withdraws, the entire court is up for grabs.” At the same time, leisure consolidates the status of the elite. “In medieval court culture as described in these texts, the nobility were the only class to enjoy such moments.”

The north-south divide?

So if you had power you also had leisure? If you look to the 18th and 19th centuries, the tables appear to be turned. English studies researcher Pia Masurczak examined travelogues by British colonists living in India and working for the East India Company. In the eyes of these businessmen, aristocrats, and politicians, leisure was often a synonym for idleness, she says. “They could not understand, for instance, why their Indian house servants were so unproductive.” A water-bearer was simply responsible for carrying water and did not also make dinner - a sign of laziness, scolded the ladies and gentlemen. “Yet it was due to the strict division of labor in the caste system.”

The question of who was thought to get through the day in a leisurely fashion and who industriously kept society running was also dealt with in academic treatises of the day. Some said the high temperatures were the reason that “southern peoples” were slower and more lackadaisical, they said. Northern climes produced more capable people, it was thought. “The English used theories like this as legitimation of their colonial power,” Becker says. In the summer, the entire colonial administration moved to Simla, a town in the foothills of the Himalaya. At nearly 2000 meters above sea level, the temperatures were significantly lower, and the officials noted keenly in their diaries how “refreshingly English” the climate was; at last they could work properly again with a cool head.

Despite this, Masurczak says, the British were not always above leisure time. Their descriptions of India and its natives swung from aversion to the “naked black creatures squatting at the doors of their huts,” as noted by writer Emily Eden in the 1830s, and the longing for a life far from the constraints of civilization. “The pleasurable smoking of a hookah for example,” Masurczak points out, “many Englishmen even in the 18th century considered that a lost cultural technique, which they themselves adopted and with which they took a small step towards the foreign world.

Breathe in, breathe out

Whether it’s hatha yoga or transcendental meditation - stressed, big-city-dwelling Westerners like to imitate foreign cultures so as to decelerate and relax. But can you meditate yourself into a state of leisure? Psychologist Minh Tam Luong shakes her head. “Individuals are told that stress is an individual problem for them to solve: ‘Do something, make an effort, so that you can keep up with the competition,’ Yet the stress itself is usually due to the individual’s attempts to live up to external demands and expectations.” And they are getting bigger.

Eighty-one high school students completed mindfulness training which helped them reduce stress in their final years of school. Photo: Gerhard Seybert/Fotolia

Luong pitched her research tent at a place once considered to be a place of leisure - schola, the Latin word for school. There, she worked on leisure’s modern sister, mindfulness. But it was not so easy to find. “You can define it as a state, a personal trait, or as a program. The important thing is a attitude of presence and non-judgement.” Luong wanted to find out whether mindfulness could help high school students to cut their stress levels in the final years of school. For eight weeks she practised the Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction Programm (MBSR) with 81 eleventh-graders at three Freiburg schools. The program was developed by mindfulness pioneer Jon Kabat-Zinn in the late 1970s. “It was important to us that this was not about doing even more work. Instead, we wanted to encourage the young people to reflect more: What is important to me? How do I want to learn?

The results demonstrated the effectiveness of the exercise, Luong says. The students who took part in the mindfulness courses felt less fearful and stressed than other students - even as many tests and exams approached. Their social and emotional skills improved, too. Luong sees mindfulness training “as a bridge which can lead to moments of leisure. For someone with high stress levels, that is not even possible.”

Into the second round

The German Research Foundation is sponsoring the collaborative research center 1015 Leisure: Borders, Temporal and Spatial Character, Practices with nearly 6.5 million euros over the next four years. This is the second round in which the collaborative research center received funding; it was launched in 2013. New subjects have been added, strengthening the contemporary link to leisure. The collaborative research center incorporates disciplines from the Faculties of Philology, Humanities, Theology, Economics and Behavioral Sciences, Environment and Natural Resources, Medicine, and the university hospitals. The computer center and the university library are also involved. The group is also helping to establish a Museum of Leisure and Literature in Baden-Baden. The speaker is Professor Elisabeth Cheauré of the Slavisches Seminar.

www.sfb1015.uni-freiburg.de