A wasteful interim phase

Freiburg, Nov 06, 2018

Germany’s last two working pits in Bottrop and Ibbenbüren shut down on December 21. Anthracite mining here is coming to an end – and with it an era, says Professor Franz-Josef Brüggemeier. With a new exhibition and monograph the Freiburg historian shows the enormous significance of coal in the past 250 years: whether for industrialisation and globalisation, the World Wars, or the stabilization of democracies and European unity. He also puts forward the argument that the age of coal was a wasteful but necessary interim period which may enable us to return to the pre-industrial principle of sustainability in the future.

Pretty colors: synthetic dyes were initially tar-based – a by-product of coke production which became the key raw material for the chemicals industry. Photo: Helena Grebe

Coal had actually been around forever. But until the 18th century, it was barely used. Once ignited, it produces smoke, soot, dirt – and a bad smell. Wood was mankind’s preferred fuel when it came to keeping warm. In fact, pre-industrial societies primarily used materials which were renewable and relied on the transformation of solar energy – that means wood, cereals, and animal products such as meat and hides. In the long term, these were resources that humans could not consume faster than they renewed themselves. And pre-industrial people used wind and hydroelectric power, for instance to drive mills. “When it comes to energy and resources, these societies were sustainable,” Brüggemeier says.

But the steam engine changed all that. It was the first means of transforming heat into motion in a big way. Before it, only humans and animals could do that – on the basis of their diet. “But for a horse to pull a plow it has to make an enormous energetic effort, and the performance is limited,” Brüggemeier explains. But once the principle of the steam engine had been understood, it became possible to produce ever-greater amounts of energy to power machines. And the raw material which represented energy in a conveniently-stored, ever-ready form – and in almost unlimited amounts, without having to grow back – was coal. “It turned out to be a powerhouse which had been untouched for centuries, whose energy was now released within a few short years.”

Light in public spaces: even after the Second World War, lanterns in the cities of Europe burned gases released by coking. Photo: Helena Grebe

A brighter, more colorful world

That paved the way for the industrial revolution and ultimately for our modern society. The mining, iron and steel industries grew rapidly after 1850; locomotives and steamers revolutionized transportation and caused a surge of globalization; coal-fired power stations produced vast amounts of electricity. But that was not all, says Brüggemeier: “Coal also made the world brighter and more colorful.” That was due to supposed waste products. At coking plants, coal was heated in airtight chambers to produce coke – a purer fuel for industry. The gases thus released illuminated European cities well into the 20th century. Tar, another by-product, was a starting-point for organic chemistry, which is all based on carbon. First it was used to produce synthetic dyes for the textile industry. “Once it was known what a molecule is and how it is constructed, the chemicals industry developed on the basis of tar – making products from detergent, to plastics, to medicines.”

Left: Chancellor Konrad Adenauer (left) signed the ECSC Treaty for Germany. It was initiated by the French foreign minister, Robert Schuman (center). Jean Monnet (right) became the first president of the High Authority, the ECSC executive.

Right: The exhibition “The Age of Coal. A European History” displays the original treaty on the foundation of the European Coal and Steel Community, the forerunner of the European Union. Photos: Lorenza Kaib

The age of coal reached its high points in the 20th century – first, the negative one: “The World Wars made clear the monstrous potential of industrial production,” Brüggemeier says. “These battles, using vast amounts of hardware, would have been unthinkable without coal.” But the experience gave rise to peace structures; this marks the positive side. “A general acknowledgement after the Second World War was that the state must play a much bigger role in solving social conflicts and ultimately in stabilizing democracy. That was particularly urgent in mining and in heavy industry, and it spilt over into many other areas.” In Germany it led to greater co-determination. From then on, there were equal numbers of members from the unions and employers in the supervisory boards of mining, iron and steel companies. And in the European Coal and Steel Community, Germany, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg and Italy agreed on the production and distribution of coal – laying the foundation-stone for postwar rebuilding and the process of European unity.

Too expensive, not competitive

But soon after, in the late 1950s, coal was in trouble in Germany. Oil and gas were cheaper and more efficient alternatives; nuclear power later joined the mix. At first it was considered important to be self-sufficient in the energy sector for reasons of national security – that was reinforced, among other things, by the 1970s oil shocks. But in the long run, coal from Germany was too expensive and increasingly unable to compete on international markets. “The state subsidies which propped up the industry for decades were ultimately far too high,” Brüggemeier says. “Financially it is absolutely the right decision to close the last pits now.”

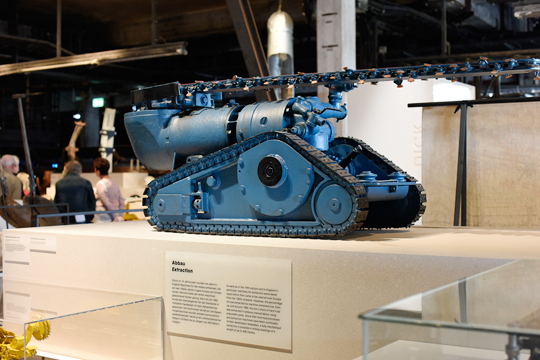

For difficult work underground: The coal cutter on tracks was a typical instrument in the phase between manual and machine coalmining. Photo: Helena Grebe

That doesn’t necessarily mean that this source of energy has had its day here - and certainly not globally. Worldwide, coal production is on the increase. The debate on coal as a finite resource – which was current until a few years ago – has been turned around, according to Brüggemeier: “Coal is still available in enormous amounts. And as long as the environmental costs arising from the release of carbon dioxide and other pollutants are not included in the calculation, it is comparatively cheap.” In addition its energy storage qualities continue to make it attractive. While yields from solar, wind and hydroelectric power are highly variable, coal can contribute to a guarantee of constant, secure supply. For that reason, Brüggemeier expects that “in the foreseeable future, imported coal will continue to be used in Europe.”

Back to sustainability

The long-term goal appears to be clear, however, at least here in Germany - away from the fossil fuels coal, oil and gas – towards renewable energies. “In some ways we are seeking to connect with the pre-industrial age by using sun, wind and water,” Brüggemeier says. “Fundamentally it will be about new kinds of networks and storage technologies replacing what fossil fuels have made possible until now.” If that succeeds, will the approximately two and a half centuries of the age of coal perhaps be the only phase of history in which people did not use sustainable energy supplies? Maybe, says the historian; yet he believes this phase had to be. “This difficult, exhausting, even wasteful, and for many people frightful interim phase was necessary for science and technology as well as democratic institutions and social achievements to develop. On that basis we can now succeed in returning to sustainability on a whole new level of permanent and safe supply of energy supplies.”

Nicolas Scherger

Adolf Hennecke, miner and Communist Party functionary in East Germany, in front of posters for the recruitment of miners. After the Second World War coal was an essential factor in the economic recovery. Photo: Helena Grebe

Exhibition information

The special exhibition “The Age of Coal. A European History,” a cooperation between the Essen Ruhr Museum and the Deutsches Bergbau-Museum Bochum, may be viewed at the Zollverein Coking Plant in Essen until November 11 2018. It has received a national and an international award.

www.zeitalterderkohle.de

Further reading

Brüggemeier, Franz-Josef (2018): Grubengold. Das Zeitalter der Kohle von 1750 bis heute. Munich.

Grütter, Heinrich Theodor/Brüggemeier, Franz-Josef/Farrenkopf, Michael (eds.)(2018): Das Zeitalter der Kohle. Eine europäische Geschichte. Essen.