A Pleasant Jolt

Freiburg, Jun 15, 2020

Not everyone who works in academia associates their occupation with leisure. Quite the opposite, they often think of the tireless research, the pressure to publish, and how they are always busy writing grant applications for new projects. Yet leisure, which is the English word for the Latin otium, was considered to be the origin of science already in ancient times, in particular by Aristotle. Since 2013, the Collaborative Research Center 1015 Otium and its researchers, who represent various fields of study and departments at the University of Freiburg, have been studying the many forms of idleness and leisure known as otium along with their historical development up to today. The CRC has recently published a special issue of their journal “Muße” (German for otium) that focuses on the relationship between leisure and science. Hans-Dieter Fronz talked to five of the researchers from the University of Freiburg who have contributed articles to this issue about their ideas of leisure (otium) in general, and leisure during the coronavirus pandemic in particular.

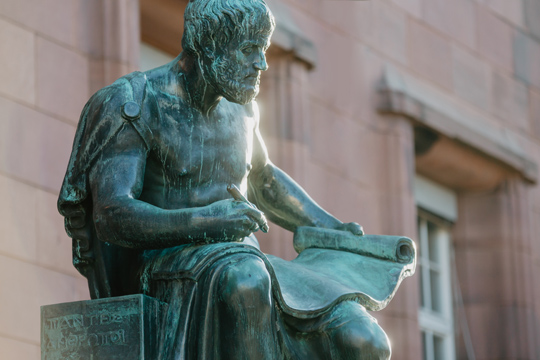

The philosopher Aristotle, whose statue also stands next to the main entrance of the University of Freiburg, once said that leisure, or otium, is the origin of science. Photo: Sandra Meyndt

According to the philosopher Dr. Jochen Gimmel (Photo: Jochen Gimmel), researchers “still enjoy a very privileged situation, also in the times of the coronavirus. I can work wonderfully from home, especially because I don’t have to teach at the moment.” On the other hand, he knows full well that researchers currently have to spend more time and effort on tackling the technical challenges of teaching remotely and remaining available to talk to students. “You couldn’t really say there are more opportunities for leisure now,” he said.

According to the philosopher Dr. Jochen Gimmel (Photo: Jochen Gimmel), researchers “still enjoy a very privileged situation, also in the times of the coronavirus. I can work wonderfully from home, especially because I don’t have to teach at the moment.” On the other hand, he knows full well that researchers currently have to spend more time and effort on tackling the technical challenges of teaching remotely and remaining available to talk to students. “You couldn’t really say there are more opportunities for leisure now,” he said.

Gimmel is a postdoc researcher in the CRC, studying how to harvest the “the potential of the concept of leisure as a critical tool” when applied to the sciences and humanities from a philosophical perspective. He juxtaposes the focuses on efficiency of an economics-dominated research with a leisure that represents research as an end in itself. He argues that, according to the philosopher Theodor W. Adorno, science is the “pleasure of cognition” and the potential freedom to let your thoughts fruitfully wander at will. Through his work at the CFC, he has become aware of just “how little time for leisure is actually offered by research today.” He has also learned the importance of resisting pressure to be more productive, and to rather give yourself time and space to be at leisure.

Have external factors become more dominant for researchers in recent decades? “That’s hard to say,” said Prof. Dr. Anja Göritz (Photo: Anja Göritz), head of the Department of Business Psychology. Göritz said she would like more time for leisure and tranquility herself, adding: “Being able to contemplate something benefits deeply from being calm, and that’s something I unfortunately don’t have enough of in my work.” Nevertheless, she said that her work as a researcher is a “source of great satisfaction.” Although the demands made on us by the coronavirus crisis may be compulsory, these necessary changes may also be an “opportunity to set a new course” in the long term regarding how researchers live and work.

Have external factors become more dominant for researchers in recent decades? “That’s hard to say,” said Prof. Dr. Anja Göritz (Photo: Anja Göritz), head of the Department of Business Psychology. Göritz said she would like more time for leisure and tranquility herself, adding: “Being able to contemplate something benefits deeply from being calm, and that’s something I unfortunately don’t have enough of in my work.” Nevertheless, she said that her work as a researcher is a “source of great satisfaction.” Although the demands made on us by the coronavirus crisis may be compulsory, these necessary changes may also be an “opportunity to set a new course” in the long term regarding how researchers live and work.

Research strives toward “knowledge for knowledge’s sake” and is the opposite of scrambling for “attention, reputation, and research funding,” Göritz said, adding that being part of the Otium and Science group of the CRC was a “pleasant jolt” and “incredibly enriching” because it let her go beyond the borders of her own field of study.

Dr. Andreas Kirchner (Photo: Andreas Kirchner) is also a postdoc researcher in the CRC. He wrote his dissertation on otium and theoria in the philosophy and theology of late antiquity. Does he believe having time for leisure still has its place in the sciences and humanities? “In brief moments of clarity, yes,” was his spontaneous response. But then he remembered what it was like to write his PhD thesis: “Whenever I was able to find time, when I didn’t have to do the things I was supposed to do and didn’t have to pursue precarious occupations, I felt incredibly privileged to be able to work with something that made me feel fulfilled, meaning my work was also sometimes leisure.”

Dr. Andreas Kirchner (Photo: Andreas Kirchner) is also a postdoc researcher in the CRC. He wrote his dissertation on otium and theoria in the philosophy and theology of late antiquity. Does he believe having time for leisure still has its place in the sciences and humanities? “In brief moments of clarity, yes,” was his spontaneous response. But then he remembered what it was like to write his PhD thesis: “Whenever I was able to find time, when I didn’t have to do the things I was supposed to do and didn’t have to pursue precarious occupations, I felt incredibly privileged to be able to work with something that made me feel fulfilled, meaning my work was also sometimes leisure.”

Kirchner believes that researchers need more opportunities to “slow down and take a step back from their work, so they can see what they’re doing with fresh eyes.” He added that criticizing research in its present form does not have to be destructive; in fact, it can be very productive. For this to be the case, however, the criteria for productivity and the paradigms of performance today need to be problematized. He learned this lesson – that freedom and leisure in the sciences and the humanities can promote a different form of productivity – from investigating the relationship between science and leisure in the CRC.

Dr. Marion Mangelsdorf (Photo: Katja Harbi), a cultural studies scholar, argues that conducting a dialogue is an element of research that can also be associated with leisure – an idea supported by such scholars as the social scientist Prof. Dr. Christina Thürmer-Rohr and the literary studies expert bell hooks. “A dialogue is something that does not think in fixed forms, but allows thoughts to develop while talking together,” said Mangelsdorf. As she and Doris Ingrisch wrote in their essay in the special issue, dialogue counteracts the “dizzying pressure to perform of academic capitalism.”

Dr. Marion Mangelsdorf (Photo: Katja Harbi), a cultural studies scholar, argues that conducting a dialogue is an element of research that can also be associated with leisure – an idea supported by such scholars as the social scientist Prof. Dr. Christina Thürmer-Rohr and the literary studies expert bell hooks. “A dialogue is something that does not think in fixed forms, but allows thoughts to develop while talking together,” said Mangelsdorf. As she and Doris Ingrisch wrote in their essay in the special issue, dialogue counteracts the “dizzying pressure to perform of academic capitalism.”

According to Mangelsdorf, a prime example of the dialogical pursuit of knowledge can be found in Plato’s Symposium. But does she also think that leisure can function if you don’t have a conversation partner? “Yes, but only in the form of a critical inner dialogue,” she said, adding that both forms seem to be very useful in these challenging times of the coronavirus pandemic. Interdisciplinary dialogue – for example, the “very good conversations” in the CRC in general and the Otium and Science working group in particular – provides the opportunity to leave the rat race of utility-oriented academia behind. That this is even possible is a new experience and a win for her.

Dr. Regine Nohejl (Photo: Regine Nohejl), a Slavic studies scholar and historian specializing in Eastern Europe, said she has the “advantage of standing on a border to cultures that are neither completely foreign nor completely familiar to Western Europe.” According to her experience, being in such a position “automatically broadens your horizon; you become more sensitive to others and how you interact with them.” She adds that this process of opening up emotionally is also related to leisure. Furthermore, the fact that the exhibition organized by the CRC about the Russian author Ivan Turgenev in Baden-Baden was also shown in Russia is an example of how “approaching themes from the point of view of leisure” can promote intercultural dialogue.

Dr. Regine Nohejl (Photo: Regine Nohejl), a Slavic studies scholar and historian specializing in Eastern Europe, said she has the “advantage of standing on a border to cultures that are neither completely foreign nor completely familiar to Western Europe.” According to her experience, being in such a position “automatically broadens your horizon; you become more sensitive to others and how you interact with them.” She adds that this process of opening up emotionally is also related to leisure. Furthermore, the fact that the exhibition organized by the CRC about the Russian author Ivan Turgenev in Baden-Baden was also shown in Russia is an example of how “approaching themes from the point of view of leisure” can promote intercultural dialogue.

Nohejl also believes that the “enforced leisure time” due to the coronavirus has unquestionably impacted how people perceive things. Despite her busy work schedule, she feels like she has found a kind of inner peace for herself, as befitting the CRC’s subject of study. She has also developed a keener awareness of the contradiction between the CFC’s research goals and the conventional academic world. Most importantly, she is truly glad that her passion for her work has been rekindled.

Collaborative Research Center 1015 Otium. Borders, Chronotopes, Practices

Special Issue of “Muße“: “Muße und Wissenschaft” (Otium and Science)