The “unusual story of a strong woman and passionate scientist”

Freiburg, May 25, 2022

As part of a course in art history, Bachelor students organized the exhibition “Between Florence & Freiburg” on the life and work of Freiburg’s first female professor of the history of art: Margrit Lisner. Her discovery of a lost work by Michelangelo in the 1960s drew worldwide attention. The exhibition is open until July 31, 2022, Thursday to Saturday 14:00 – 18:00, in the project room at the Uniseum, the Museum of the University of Freiburg. In conversation with Franziska Becker, course leader Dr. Andreas Plackinger and student Katharina Ramstein spoke about the highlights of the exhibition and the challenges they faced in planning it.

Art historian Margrit Lisner taught at the University of Freiburg for nearly 30 years. Photo: Willy Pragher: Portrait photo Margrit Lisner, 1964. State Archive Baden-Württemberg, State Archive Freiburg.

Art historian Margrit Lisner taught at the University of Freiburg for nearly 30 years. Photo: Willy Pragher: Portrait photo Margrit Lisner, 1964. State Archive Baden-Württemberg, State Archive Freiburg.

Margrit Lisner discovered a lost work by Michelangelo in 1962. How would you describe the importance of Professor Lisner and her work to art history?

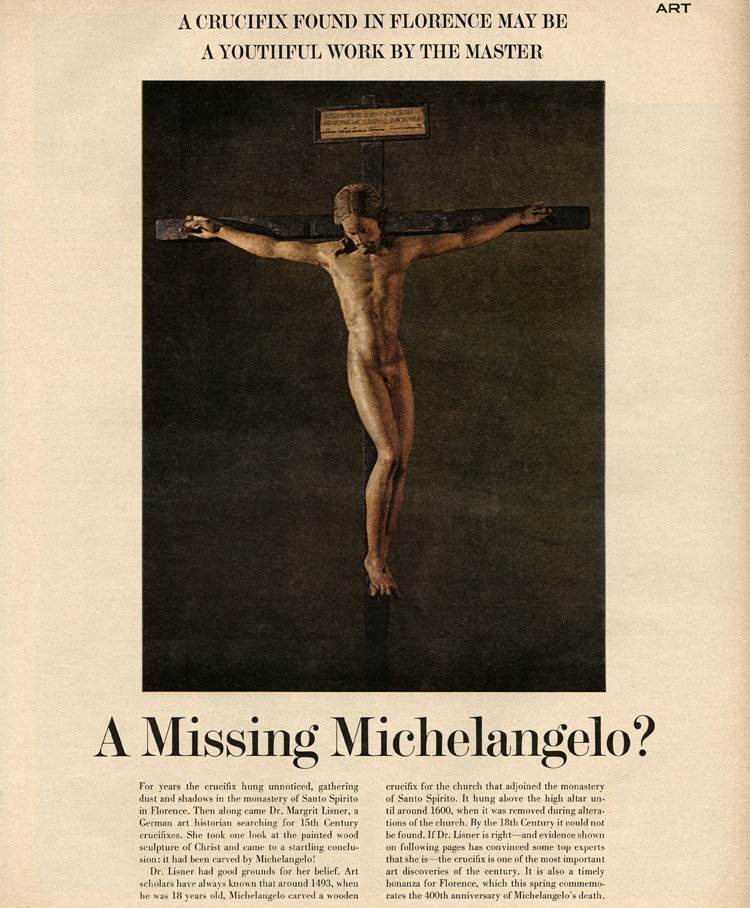

Andreas Plackinger: Margrit Lisner was the first female professor of art history at the University of Freiburg and in fact one of the first female professors of art history in Germany as a whole. She taught here in Freiburg for almost 30 years. Afterward, she donated her academic legacy to the Institute of Art History. It was a real treasure trove and naturally the ideal starting point for our project. Lisner became famous within her field and beyond mainly because of her rediscovery of a lost early work by Michelangelo. This work, the crucifix from the Basilica di Santo Spirito in Florence, is an astonishingly graceful and utterly sensuous figure of Christ and is looked at in great detail in our exhibition. Lisner also researched many other Renaissance artists, for instance Donatello and Leonardo da Vinci. Margrit Lisner would have been 100 years old in 2020. So there were many reasons why it was worth dedicating an exhibition to Lisner as a respected researcher.

Katharina Ramstein: Yes, the course during the 2019/2020 winter semester was the right opportunity to tell the unusual story of a strong woman and passionate scientist.

Do you know then how exactly Margrit Lisner discovered the work by Michelangelo?

Ramstein: Florence was at the heart of Margrit Lisner’s life as an art historian and her primary interest was sculpture. For this reason – as far as possible – she spent every free minute in Florence. On her hunt for interesting works for her research into wooden crucifixes she traveled alone by Vespa in the late 1950s to some of the most remote churches in Tuscany and looked at every crucifix she could find. Then in 1962 she discovered an inconspicuous crucifix that hung above a door in a passageway in the convent of Santo Spirito. Her many years of research into the wooden crucifixes of Tuscany meant that she recognized it as a lost early work by Michelangelo.

Plackinger: Here can be added that a disfiguring layer of paint, applied subsequently, quite spoiled the effect of the sculpture. Incidentally, the monastery of Santo Spirito is located in the center of Florence, and yet the many specialists in Florentine sculpture had overlooked the work. Lisner's discovery caused great anger and envy among some of these specialists.

The start of the exhibition had to be postponed until 2022 because of the pandemic. What was the private view at the end of April like for you?

Ramstein: Two years is a long time when you’re studying, and we’ve had to deal with a lot of new things. So the course and the exhibition were a bit overshadowed. As a result, we students are even happier to present our exhibition at last, in fact I had started to doubt it would happen. It’s a well-deserved and successful conclusion to the rather experimental course after more than two years.

Plackinger: I thought it was a pity that it wasn’t possible for all the students who were involved in the project to be at the opening. But those who were there and who helped to set up the exhibition with me had gone through every stage of creating an exhibition. The celebratory mood at the private view was like a reward for the stamina forced upon us by the pandemic.

In 1964, the American reportage magazine 'Life' reports on Lisner's Michelangelo find. Photo: First page of the article 'A Missing Miachelangelo?', Life, 21.02.1964, p. 46. Art History Institute, Library

In 1964, the American reportage magazine 'Life' reports on Lisner's Michelangelo find. Photo: First page of the article 'A Missing Miachelangelo?', Life, 21.02.1964, p. 46. Art History Institute, Library

Can you outline how a museum exhibition is put together as part of a course?

Ramstein: At the start of the course, Mr Plackinger explained to us everything that had to be done. In the first few weeks we began to read the academic writings of Margrit Lisner, from her first publication, her dissertation on Luca della Robbia, through to her last, an article on Michelangelo’s Tondo Doni. We got to know Margrit Lisner as an art historian and academic, saw how she approached works of art and how she worked. We divided the literature up so that each of us read some of it and summarized it for the group. We also sifted numerous boxes of letters, postcards, working materials, photographs and publications. Then in various teams we tackled the range of tasks.

Plackinger: The editorial team compiled lists of items and texts and collected and corrected the signs for the exhibition area. The exhibition curatorial team dealt mainly with preliminary choice of objects and later with practical questions about setting up the exhibition. The press team wrote a press release and conducted interviews with contemporaries, two of Margrit Lisner’s PhD students. And the entire group discussed findings each week at meetings and all major decisions were taken jointly. I remember that it took a lot of time to agree on the title.

Ramstein: And we were very lucky, because Gisela Bonfig, the Institute of Art History photographer, supported us by taking on the graphic design and printing.

Such a large project involves a lot of tasks. What did you find easy? What was challenging?

Ramstein: It was a major challenge to look through Margrit Lisner’s legacy and seek out what we wanted to display in the exhibition. On top of that were tasks that required a lot of time, such as reviewing all the off-prints she’d collected over the course of her life. But even though it all took a lot of time and a fair bit of stress, it was an incredibly enriching and beautiful experience to be part of an exhibition from start to finish while studying.

Plackinger: We’ve visited the project room at the Uniseum where the exhibition will be held many times. All the students were able to get to the heart of what we need to consider in our exhibition and what advantages and disadvantages there are to the exhibition room. There were no teething problems for anyone when discussing the initial ideas for the graphic design with the institute’s photographer, who was very committed to the project. I think the greatest challenge was to imagine at the start where the journey would go as regards contents and visuals, when we only had the overarching theme, the location of the exhibition and a rough timescale. The more tangible it became, the more fun everyone had.

What is your personal highlight of the exhibition?

Plackinger: My favorite item is an issue of the American magazine Life from 1964. It shows Margrit Lisner in an article with the title “A Missing Michelangelo?” The same magazine also has articles on the Beatles and the assassination of John F. Kennedy, so it’s strange company for an art historian from Freiburg. But it shows what a sensation her Michelangelo discovery was back then.

Ramstein: My personal highlight, and I think my fellow students would agree with me, was the moment when the large-format image of the crucifix was placed on the wall, giving the square vestibule a sacred atmosphere. A massive surprise and another highlight is the tiny collection of East Asian art which we didn’t expect someone who had spent all her life working on Italy to have.