Tracing Paths of Progressive Spirits

Freiburg, Feb 08, 2019

A city's history is best brought to life by becoming immersed in the biographies of people from days gone by. A group of event organizers, among them the University of Freiburg's Department of History – Regional Section, is aiming to do just that. Researchers are holding a series of lectures called "Auf Jahr und Tag" (To a Year and a Day). These talks trace lives in Freiburg during the early modern era. The subjects are individuals from the arts and religion, research and social welfare, politics, and those who worked to resist the Nazis. Anita Rüffer went on the trail of Freiburg's progressive spirits.

A late honor: A street in the new Freiburg district of “Brühl-Güterbahnhof” has been named in memory of the researcher, who was driven by the Nazis from Germany in 1933. Photos: Sigrid Gombert, University Archives, Freiburg/UAFD001301393

Martin Waldseemüller – a cartographer who did not depict reality

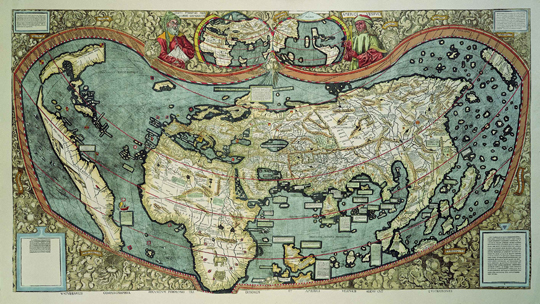

Born in Freiburg between 1472 and 1475, cartographer Martin Waldseemüller received media attention five hundred years after his death. His map of the world dating back to 1507 showed the Pacific Ocean for the first time. It also presented America as a continent separate from the rest. This work of Waldseemüller's was included in UNESCO's Memory of the World register in 2005. Only a few of the one thousand wood-block prints of the map have survived through the centuries. An Upper Swabian noble family sold one of them to the Library of Congress in Washington for ten million US dollars in 2001. Dr. Martin Lehmann has even held the original in his hand. He also made sure that there is a memorial plaque on Löwenstraße near Collegiate Building III. It features a faithful copy of the map made by the famous student of the University of Freiburg. Lehmann came to view Waldseemüller as a "man between two worlds." He had one foot in the Middle Ages and another in the Age of Discovery. New regions of the world were emerging, the printing of books began, and stirrings of the Reformation were perceptible. Both worlds left their mark on Waldseemüller's work.

A productive team

It's a proven fact that Waldseemüller – originally called Waltzenmüller – matriculated as a student of Mathematics and Geography at the University of Freiburg on 7 December 1490. His date of birth can be approximated from that. He grew up in Freiburg, where his father, Konrad, a butcher, settled in 1480. Konrad must have made enemies there. In 1492, he was murdered in front of his guild house on what is today Kaiser-Joseph-Straße. His son's career went on nevertheless. After finishing his studies, Martin went to St. Dié with a fellow student, Matthias Ringmann of Alsace. It was there that Waldseemüller died on 16 March 1520. The two colleagues worked together closely. Waldseemüller was the cartographer whose world map of 1507 reshaped ideas about the globe. His colleague wrote an in-depth text to accompany the map. It was Ringmann who posited the name "America" for the new continent – after seafarer Amerigo Vespucci – who had explored the east coast of South America and written a report about the "New World."

According to Martin Lehmann, the duo had never known free, unhindered basic research, or the imperative to map new findings about the world as accurately as possible. "Waldseemüller concealed what it was really like," says Lehmann. He mentions "political maps" – tools of commercial interests that were shackled by financial dependencies and political ties. The Portuguese, for example, wanted to keep the Spaniards away from their trading routes in order to avoid placing their wealth from the spice trade at risk. Waldseemüller included non-existent barriers, mixed information from ancient sources with the new, and skewed proportions. Even the depiction of America as a separate continent could have initially been a "fake," meant to mislead the Spanish.

In 2005, Martin Waldseemüller’s map was included in UNESCO’s Memory of the World register. Photo: University of Freiburg

Bartholomä Herder – Founding publisher and canny businessman

When someone hears the name "Herder" in Freiburg, they immediately see the distinctive "Herderbau" (Herder Building) on Habsburgerstraße. Built by architect Carl Anton Meckel at the start of the 20th century, the red building is seen as testimony in stone to a publishing dynasty. Started by Bartholomä Herder a century before the "Herderbau" was built, the publisher is still a going concern today. Manuel Herder is the sixth generation of the family to run it. Bartholomä never did get to see the splendid domicile himself. He bustled through life until 1839, when he died at age 65. By then, he had long been at the center of Freiburg society.

The son of a tailor, cloth merchant, and alderman from Rottweil, Bartholomä wasn't born a bibliophile. Herder's mother came from a family of butchers. His parents sent the eldest of their five children to the monastery school at St. Blasien. Bartholomä was supposed to have become a priest. But he was drawn into the world of books instead. He became the court bookseller at the Meersburg "Residenz," or palace, of the prince-bishop of Constance in 1801. In 1806, secularization that included comprehensive, reorganization of the principalities, or mediatization, brought Herder's career to an abrupt end. Meersburg shrank to an insignificant backwater town. What was Herder to do? Resettle in Karlsruhe, the capital of Baden? Herder chose Freiburg because of the Catholic environment of its university. There, he opened an academic bookshop. The director of the archive of the Archdiocese of Freiburg, Christoph Schmider, explains that this forced Herder into printing and publishing simultaneously. He leased the monastery's printing press at St. Blasien, which was administered by Freiburg after secularization.

House authors and best-sellers

Even today, Herder publishing still carries the label "God's own publishing house." It printed almost every book a Pope had written. The company's founder must have been an intrepid businessman. He expanded the publishing house's selection to history, art, and works of music. Lithography that Herder brought in from France gave him better and less costly printing technology. This allowed the printing of entire galleries of pictures to illustrate reference works, for example. Herder founded his own art institute, where painter Franz Xaver Winterhalter was among the artists to be trained there. According to Christoph Schmider, the father of two sons and six daughters should be imagined as a "networking talent." Freiburg's dignitaries founded a literary society which met at Herder's house to read the valuable editions together. Several people from this circle became house authors of Herder publishing. Karl von Rotteck's "Allgemeine Geschichte" went on to become a best-seller. Schmider says the publisher, "really got around, especially, during the Napoleonic Wars." As director of the imperial-royal military press, he was represented at peace negotiations in Paris and at the Congress of Vienna in 1814-1815.

Institutes of the University of Freiburg are housed in the distinctive “Herderbau” on Habsburgerstraße. Photo: Sandra Meyndt

Georg Schneider – the forgotten architect

Georg Schneider must have known how to network as well. "He received many of his commissions through personal connections," explains art historian Stephanie Zumbrink. Schneider was born in Eichstetten in 1809. The architect who was firmly rooted in the Protestant community had countless contacts. He wasn't just occasionally the university's architect. As a member of the the administrative board of the Protestant foundation, he was their architect as well. From 1842 until 1877, he was also responsible for building training at the vocational school. And he cooperated fruitfully with the Karlsruhe architect and university teacher Friedrich Eisenlohr, under whom he had studied. Eisenlohr built stations and signalmen's houses for the Baden Railway as well as Ortenberg Castle near Offenburg, and the "Festhalle" which once stood in Freiburg's "Stadtgarten." Schneider managed the construction of these, which by no means implies that he did not realize many of his own designs in the city of Freiburg and its environs, which were both rapidly growing.

Scarce sources

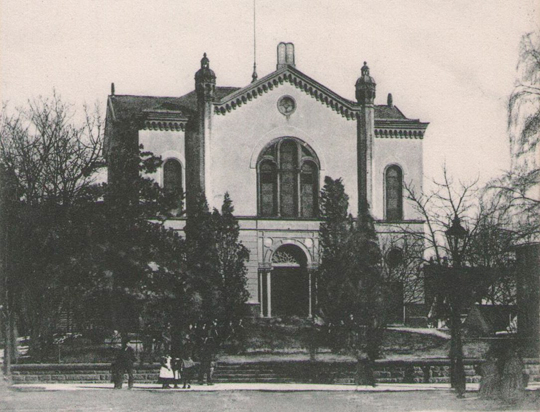

There isn't much of that left. That could explain why a very busy Georg Schneider, who died in 1883 in Badenweiler, is barely known to the public at all today. Among his projects were many synagogues – such as those in Freiburg, Kippenheim, and Müllheim, the university buildings on the Natural Sciences Campus which were flattened by bombs in both world wars, as were those of the Protestant foundation, the "Stiftbauten." But Schneider's style – which replicates English Tudor Gothic – can still be studied at the "Colombischlössle," which is now home to Freiburg's Archaeological Museum. Otherwise observers find a mix of Roman, Gothic, and Byzantine elements. His house on Gartenstraße, where he lived with his wife and nine children, still stands today. According to Stefanie Zumbrink, his influence has yet to be researched. Little is known about him as a person. From rather meager sources, it is known that he first apprenticed as a carpenter before attending a drafting school in Freiburg and going on to study at Karlsruhe "Polytechnikum." Many of his plans still exist, including a collection of simpler designs that he made for his vocational school students. He may not have been a star architect such as Friedrich Weinbrenner in Karlsruhe or Karl Friedrich Schinkel in Berlin, but according to Zumbrink, "he was technically up-to-date and a good construction manager and teacher."

Georg Schneider designed the Freiburg Synagogue that was destroyed by the National Socialists in 1938. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Bertha Ottenstein – Research pioneer and maverick

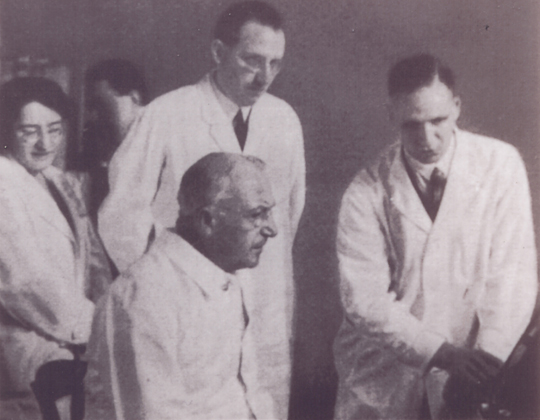

Her name has been known to the university public since 2005, when the school's award for the promotion of gender equality was named for Bertha Ottenstein. Karl-Heinz Leven, Professor of Medical History at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, views that as a great success. Ottenstein was a medical doctor and chemist, with two doctorates. At the beginning of the 1930s, she was the first woman to do post-doctoral work in dermatology. This fact, along with her research into the skin's protective layer – the acid mantle – gave her field an innovative boost. Back then, a big push was just what the subject known as dermatovenerology needed. The field was tinged with immorality because it was linked to the treatment of venereal diseases, which had been spreading like an epidemic since the turn of the century. "No respectable doctor wanted to have that kind of practice. The patients weren't even allowed to greet their doctor in public," Leven explains. But the subject was gaining ground. The military bordellos of World War One had been breeding grounds for venereal disease. Following Germany's defeat and demobilization, a number of clinics were founded. New horizons in terms of content and treatment opened.

Expulsion after 1933

A progressive spirit was at work under the supervision of clinic director Georg Alexander Rost at the Freiburg Skin Clinic, which had moved to the military hospital on Hauptstraße. The clinic is still there today. Rost had recognized the potential of his assistant, Bertha Ottenstein. He couldn’t have cared less that she was a woman or a Jew and promoted her scientific career. Her interdisciplinary research in close proximity to clinical practice was ahead of its time. Yet things didn't go well under the Nazi regime for long. Not for Rost either. Ottenstein was forced to leave the university in 1933 because of her Jewish ancestry. It was an imputation that the Nazis imposed on her. The youngest of six children, Ottenstein was born into an assimilated, secular Nuremberg merchant's family in 1891. For her, being Jewish had never been important. She was "as German as you can possibly imagine," says Leven. The single, childless woman must have felt even more alienated when she emigrated and began an odyssey that took her via Budapest and Ankara to the US in 1945. Despite good contacts within the field of dermatology, she never really established herself in America. Her attempt to pass the required US medical licensing exams failed several times due to limited knowledge of English. In the 1950s, she filed a compensation claim in Germany. Yet her life ended in tragedy. In 1956, she died in a swimming accident on the same day she was notified of redress from Germany.

Claim at eye level: Bertha Ottenstein was the first woman to do post-doctoral research at the University of Freiburg. Photo: University Archives, Freiburg/UAFD001301394