The Reformer

Freiburg, Oct 27, 2017

To this day it is contested as to whether Martin Luther really nailed his 95 theses on the door of the Wittenberg Castle Church on October 31, 1517. What we do know is that his protest rocked the world in the late Middle Ages. His ideas resonate even today – both within and beyond Europe. Freiburg researchers at the University of Freiburg have approached the person and reformer Martin Luther. A mosaic of ideas gathered by Stephanie Streif.

Illustration: Svenja Kirsch

Illustration: Svenja Kirsch

Songs for the masses

German “Schlager” or pop music didn’t just appear at the beginning of the 20th century with the rise of stars such as Marlene Dietrich or Hans Albers throughout the clubs in Germany. It already started 500 years ago as Martin Luther’s reformation hymns spread like pop music. Henrike Lähnemann, professor for German Medieval Studies in Oxford, England and fellow at the Freiburg Institute for Advanced Studies (FRIAS) at the University of Freiburg explains how that worked: “Catchy melodies, vernacular song lyrics and an emotional message: Printing, translating and singing were Luther’s main methods of distribution that he cleverly combined to pass along his reformative ideas.” Before Luther came along, theological context was conveyed in Latin. Prayers, hymns, the Bible – often inaccessible, at least to the larger masses. With Luther everything changed.

Pamphlets, song sheets and devotional texts were distributed in places where people could read: in privileged circles, but also in schools because Luther had a pedagogical mission as well: The youth should spend their time on godly matters. So-called ‘bürger’ or citizens as well as students were multipliers that merrily passed along Luther’s ideas to society. Lähnemann explains how a little song turned into a protest song for instance, when a Catholic priest entered the pulpit and the congregation just started singing because they didn’t want to listen to him. Singing was also a subversive moment: The prince of a Catholic territory forbad all of Luther’s texts for fear of a revolt. His subjects were allowed to sing because, after all, songs transport Biblical meaning. “The songs were like a submarine. Years later the prince joined the Reformation,” says Lähnemann.

The Reformation isn’t a historical event, but rather a continuous process. In order to illustrate that fact, Lähnemann, together with a group of students, started a blog in which they list lectures, workshops and live events happening in the year of the Reformation. Readers can also find transcripts and transitions of the Reformation pamphlets there. “The blog is an attempt to illustrate online the liveliness of the media debate at the time of the Reformation.”

Sexuality without sin

Martin Luther has long been accused that he didn’t have a grip on his own sexuality. After all, he was a monk first, left the Augustinian order and later married Katharina von Bora with whom he had six children. “During Luther’s time, sexuality was connected with the notion of disorder in intellectual circles,” explains theologian Prof. Dr. Magnus Striet. And everything that was disorderly was considered sinful. For young Luther his reorientation wasn’t easy either. Should he switch to the status of a married man? Should he not? In the end he decided to do so and – as letters prove – he was surprised how much joy it brought him to be together with a woman, including sexually. It poses the question as to how Luther managed to suddenly redefine physicality in a positive fashion. And that publicly. “Piety in the Middle Ages was associated with people’s fear. Fear of God. Fear of eternal damnation,” explains Striet. Luther managed to break away from this dark notion of the world. “Or rather: He came to the conclusion that people themselves can do nothing for their salvation because it is the work of God, including man and his sexuality.”

Striet found it interesting that already during Luther’s lifetime there was a struggle around sexuality that was embedded in the overall Reformation movement. As background: Not only monks such as Luther but also a multitude of nuns left their orders at that time. It was a real political issue, according to Striet. And while the anti-Reformation movement propagated chastity, Luther valued sexuality as something deeply human. He did not, however, question the gender roles that were current at the time. In theory, he equalized gender relations in which he announced joint priesthood for all believers, including women, and replaced the clerical system with the family as the main institution within society, but the structures remained patriarchal nonetheless. Luther got into trouble with his Biblical literalism, says Striet: “Sticking strictly to the text usually means that you don’t rattle that which is – because of the hermeneutic glasses you are wearing while reading.”

Katahrina von Bora

Katahrina von Bora

The 500th birthday of Katharina von Bora was celebrated with a postage stamp in her honor.

Photo: laufer/Fotolia

Facets of freedom

Up until recently the theologian Prof. Dr. Karlheinz Ruhstorfer lived in Dresden. While he was there, he experienced how thousands of people would take to the streets every Monday to protest against refugee policy while shouting right-wing slogans. “For the first time I had the feeling that our liberal freedoms were no longer something to take for granted.” In Ruhstorter’s view, these liberal freedoms have something to do with Martin Luther too. “In Protestantism the spirit of freedom emancipated itself.” That is not to say that freedom is an invention of Protestantism. Apart from Catholic France in which the Enlightenment led to a break between religion and the bourgeoise political commonwealth, the religious and political landscapes in Switzerland, the Netherlands, Great Britain and the United State melded together: “Liberal freedoms that characterize the West emerged for the most part within the Latin church -- and primarily in those areas that were Protestant at first.” It was different in France, however: The enlightened religiously neutral state tried to draw religious boundaries.

Luther came from the monasticism of the late Middle Ages and studied under Wilhelm von Ockham who emphasized man’s freedom of will. What was equally formative for him was mysticism that locates the godly principle within man himself and not in external acts such as a liturgy. Modern self-assurance of man finds its origins with Luther. But this kind of freedom did not last forever, but rather became institutionally contained within Protestantism over the centuries. Not much is left over of the great freedoms of 19th century Lutheran Germany. Why? Because the state took over. The nation state and Protestantism melded into one entity, which, nationally charged, also mobilized against the Weimar Republic’s brand of democracy in the 20th century. A development that, during the Third Reich, led to a portion of Lutherans serving the national socialists and even regurgitated Luther’s hatred for the Jews. During this era, “Luther” lost his innocence, says Ruhstorfer. Luther was a child of the times and isn’t easily modernized to match today’s thinking. “He had great ideas. And these ideas also had a dark side.”

A formable fortress

Amazing what you can read into (or interpret out of) a church hymn. When Martin Luther wrote the choral “A Mighty Fortress is Our God,” he was only thinking of the relationship between God and His believers. In his religious point of view, the believer had to fight daily against evil, the devil, sin. God was his refuge, a “mighty fortress”. “In order to describe that inner struggle, Luther relied on military imagery in which words such as defense, weapons and enemies are used,” says Michael Fischer, Managing Director of the Center for Popular Culture and Music. Fischer took a closer look at Luther’s trusty song whose message has become more and more secularized over the centuries. “Things got turned on its head,” explains Fischer. Up and down were turned around. You weren’t just evil if you were in hell, but also if you were a denominational opponent and later French or Russian. The song was first denomenationalized and then later nationalized.

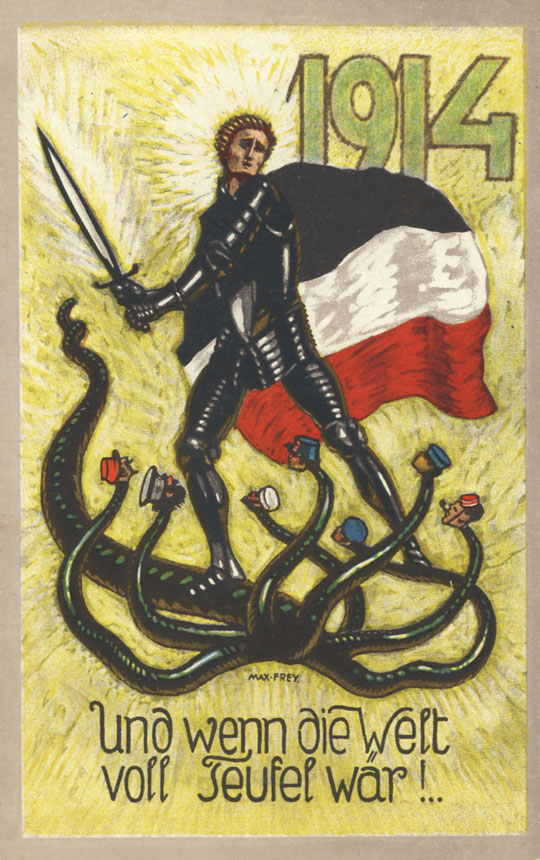

Poetically speaking, Luther’s song is quite something. Although it was written in the 16th century, it still worked 400 years later. Just differently. The anti-godly power is no longer the devil, but the hereditary enemy – that is, France. Ethically however, Fischer argues, the text opened “the floodgates for abuse”. During World War I, “A Mighty Fortress is Our God” was widespread. The song was still being sung of course, especially – at least partially and in modified form – printed on postcards, in books, on brochures and quoted in speeches and sermons. Luther’s choral even exists on shellac and on real Rosenthal porcelain. A wall plate from 1917 is hanging on the wall behind Fischer’s desk. On it you can see Luther’s head and an inscription from the song. What amazes the Freiburg scientist in particular is how widely spread the song was: “It is like a stormy wind’s howl, the mighty fortress choral / the German oak’s glorious roll, in suffering and night and war’s weather sprawl”, a verse from a poem released on October 31, 1917 in the Liller war newspaper, just in time for the 400th anniversary of Luther’s theses nailing. It doesn’t get any more nationalistic than that.

During the First World War - 400 years after the hymn “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God” was penned - it was used for nationalist propaganda.

During the First World War - 400 years after the hymn “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God” was penned - it was used for nationalist propaganda.

Source: Michael Fischer Collection

Hymns during the church service

From a contemporary perspective, Martin Luther seems to be a revolutionary who quickly turned one church into two. But that kind of clean cut didn’t actually happen, not even in the form of the church service. Ask the person who should know: Freiburg musicologist Prof. Dr. Konrad Küster. The notion that Luther gave the congregation a voice during worship is wrong, he says. “That is a belated project from theologians in the 18th century who, through the course of the Enlightenment, wanted to rid themselves of the Baroque bombast that was the great church music.” What’s interesting: The 18th century Lutherans reacted to the strict Calvinism in whose church services only songs were sung: Adaptions of the Biblical psalms. It seemed plausible to the Lutheran theologians and they accused Luther that even he preferred such simple music. “Luther planned to translate Latin hymns into German, but not with the intention of letting commoners sing during worship,” explains Küster. Even Luther prefers to leave the singing up to the pros during mass.

Unlike today, the entire mass was sung back then – with the exception of the sermon itself, which was spoken. Typically the priest would alternate singing with the local schoolmaster and his students. And the congregation was there to listen. Luther didn’t see the need to do anything regarding church music. On the contrary: The old church service hymns were integrated into the modern mass. Why change it? The Gregorian choral chock full of Biblical references from the early Middle Ages, for example, fit right into Luther’s image. And the compositions by Josquin des Préz, a Catholic himself, sounded to Luther like God’s word. It wasn’t until the end of the 17th century about 150 years after Luther’s death that a true congregational hymn during worship developed. “The transition happened over a long time span,” says Küster. And the many songs that Luther translated, composed and wrote? “They were for school, for the home and even for the street, but not really for church.” Personal faith meant much more to Luther than a church service anyway.

dbbda2b7b8dc9b8a56ffd342556903cb

An early commitment to Brexit?

What does Martin Luther have to do with Brexit? At first and second glance, nothing at all. But it’s worth taking a third look. Because without the person Luther and the enormous effect that the Reformation had in the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation, the reformative movements could not have infiltrated neighboring countries. Even in England although King Henry VIII rejected Luther’s teachings his entire life, the historian Prof. Dr. Ronald G. Asch explains: “The Reformation in England harks back to a royal decision by Henry VIII. Theologically speaking, England’s king was no Protestant – it was much more about royal church rule.” In order to complete the separation with Rome, Henry VIII enforced a series of Reformation laws in the 1530s, one of which was the “Act in Restraint of Appeals’ in 1533. It claimed “This realm of England is an empire ...” Or, to put it another way: We are subject to no one. No worldly or spiritual rulers and most certainly not the Pope.

The conservative British parliamentarian John Redwood, an avid European Union (EU) critic, made this quote the title of a blog post he published in June 2012. According to Asch, Redwood and other Brexiteers believed the subjugation to Brussels would be a betrayal against English constitutional tradition as justified by the Reformation: “It was the break with Rome that established the thinking of the King-in-Parliament’s absolute sovereignty that remained the foundation of England’s unwritten constitution up to the second half of the 20th century.” This absolute sovereignty should be reestablished with Brexit. The pride in specifically English traditions played an important role during the anti-EU membership campaign. Those against Brexit had nothing with which to go up against such a historical argument. But Henry VIII is now being drawn in once again, this time by those opposing the current Prime Minister Theresa May – in the debate around the Brexit law. They claim May seeks absolute rule as Henry VIII did back then. “It is meant polemically, of course,” says Asch. “But it makes it clear that history has an impact even today.”

Heinrich VIII.

Heinrich VIII.

England, an empire: Henry VIII broke with Rome and the Pope in the 1530s - yet throughout his life, he rejected Luther’s teachings.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons