“Organic produce is not better per se”

Freiburg, Aug 01, 2017

Strawberries in December, tomatoes from Holland - Some estimates say the food each person in Germany eats comprises about one-third of his or her environmental footprint. The effects of consumption are a most pressing issue in the places they are multiplied - towns and cities. But can a city have any influence on food in order to become more sustainable?

Photo: Jürgen Gocke

Sustainability plays a big role in the mission statements of many German cities and towns. To reduce carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, they are pressing forward with measures aimed primarily at energy supplies and at traffic and transportation. A new project, “communal food systems as the key to comprehensive-integrative sustainable governance,” known by its German acronym, KERNiG, goes one step further. The project partners are analyzing the towns of Leutkirch (Allgäu region) and Waldkirch (Breisgau) to find out how food systems can be influenced and altered by the policies of local government. Sonja Seidel spoke to Heiner Schanz, head of Environmental Governance at the University of Freiburg and KERNiG spokesman, about the situation in the project communities and about what characterizes sustainable food policy.

Dr Schanz, why is it that hardly any towns have taken a close look what the food their inhabitants eat?

Heiner Schanz: Firstly, it’s because the food we eat is a private matter. Everyone wants to decide for themselves what ends up on their plate. And then, food and food marketing are a very complex subject. An average supermarket has some 12,000 products on its shelves. Around 9,000 of those are food items, which are subject to time constraints such as shelf-life, seasonality, and availability. Furthermore, there is absolutely no data base; we don’t know just how much is eaten in a town, what is eaten, nor where that food comes from. It is much easier to collate statistics in matters of energy and mobility. All these things mean that we have recognized that food is important - but we have not tackled it actively.

“How, where, when something is produced and processed - that is the key to sustainable nutrition; but it is still only one aspect of the problem,” says Professor Dr. Heiner Schanz. Photo: Patrick Seeger

If people don’t want others telling them what to eat - where does the KERNiG project start out?

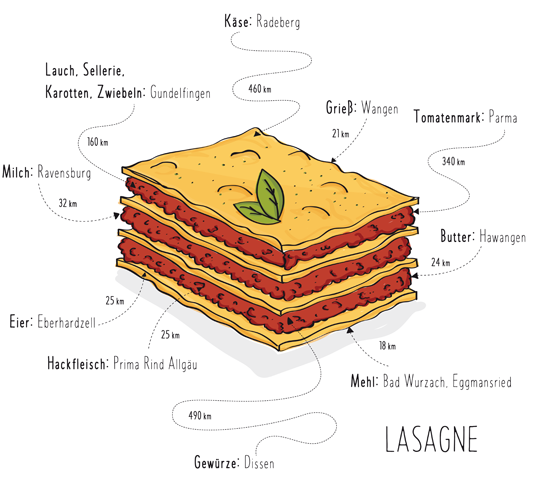

We start with the variety of food-related activities and relationships in the communities. The food markets are global, international, and regional - but in fact, it is the responsible people in the towns themselves who set the tone for local eating habits. Leutkirch for instance has 23,000 inhabitants. Currently there are 400 people in the local authority, in companies, clubs, and initiatives - right down to individuals - involved in production, processing, supplying and disposing of food products. Many of them don’t really even know about some of the others. So we are first of all trying to understand how the individual actors are interlinked and what would happen if we could bring them together systematically via joint activities or a common mission statement. At the heart of our project is the question of whether local authorities can target networks to better organize the food supply.

How do you get each actor involved?

That is a big challenge; each of the towns is an equal project partner. That means in principle that we have more than 45,000 participants. In a first step we worked with panels of experts in which the local authorities’ contact persons - many of them companies in the business and citizens’ initiatives - had their say. We have also held public forums because we didn’t want to shut anyone out; we wanted everyone to get the opportunity to thing about and work with the project. On the basis of the discussion results, the local authorities are working on concrete measures to be implemented in the next phase of the project and which will be overseen by the research partners.

The women in Leutkirch analyzed the meals they offer in their catering service. Where do the products come from, and could they be replaced with local produce? Image: Stadt Leutkirch

Do the people of Waldkirch and Leutkirch now all have to shop at the organic food store?

Not necessarily. Organic produce is not better per se than conventional produce - even if that is often claimed in public debate. With regard to sustainability, we need to move away from individual products and look at eating habits. It quickly becomes clear that supposedly “better” alternatives such as a vegan diet don’t turn out any better in the overall comparison. Because alternative products such as oils, fats, and soja bean products cannot be produced regionally in the amounts required and to meet year-round demand. That has effects on the environment. If an entire city or if all of Germany were to eat purely vegan, we would certainly have a sustainability problem.

What can the average person do?

Cook at home and regularly take time - including shopping time - for food; that raises awareness of the complex forces at play. How, where, when something is produced and processed - that is the key to sustainable nutrition; but it is still only one aspect of the problem. The other question is how the effects of individuals’ eating habits are multiplied in societies - on how much has to be produced and processed for everyone to have enough food for the whole year and be healthy. Studies show that a varied diet - including moderate consumption of meat and luxury foods mixed with seasonal and regional products - has a bigger potential to reduce our environmental footprint than, for instance, exclusively eating organic foods. And in particular, that means throwing as little food away as possible.

Information on KERNiG:

www.kernig.uni-freiburg.de