Off to America!

Freiburg, Dec 14, 2017

More than five million Germans emigrated to North America in the 19th century. Prof. Dr. Rüdiger Glaser from the Institute of Environmental Sciences and Geography is convinced that they not only fled from poverty, war and revolts. He and his team analyzed among other things migration and population statistics, weather data and the price of wheat in the southern German area and came to the conclusion that up to 30 percent of those who migrated can be traced back to climate extremes. Sonja Seidel sat down with Glaser for a chat about the connection between climate, rising wheat prices and migration.

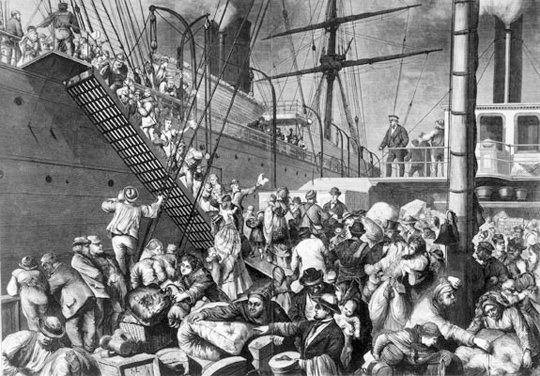

German emigrants boarding a ship to New York City/USA around 1850. Source: Wikimedia Commons/public domain

Mr. Glaser, the first Germans started emigrating to America around 1700. Why have you concentrated on 19th century emigration?

Rüdiger Glaser: There are various reasons why this particular century is of great interest from a scientific perspective. For one, emigration from Europe to North America during this time was historically the largest in terms of absolute numbers and according to today’s dimensions. For another, the Little Ice Age spilled over into this century; a natural climate variation that created cooler temperatures. It merged with man-made climate changes. And finally, politically a lot was going on then: the Napoleonic Wars, revolutions, the foundation of the German empire. In addition, a lot of social change and the transition from an agrarian to an industrial society.

What role does climate play in emigration?

In the research literature, migration thus far has been explained mainly by political and social changes, for example with demographic pressure, which of course applies. As we have shown in our study, climate was an indirect driver behind the emigration wave. We discovered that up to 30 percent of the migration rate can be traced back to climate variations at the time. There was therefore a causal chain of events linked to climate, harvest size and price developments that affected migration.

f18766349728704de09aa21df7696567

How did the chain of events work?

The weather pattern, for instance, impacted the amount of wheat harvested. So in 1846 a very dry and hot summer led to a very bad harvest. That led to an increase in food prices. A lot of people started to starve. A latent poverty and lack of perspective ensued, a bunch of factors that put so many people under pressure that they had to leave the country. Another pull factor, that is the incentive, was the image people had of life in America.

They hoped to live a life of freedom?

Religious, political and economic freedom was an important motive. After the Congress of Vienna in 1815, a lot of people experienced increased repression in Germany. Democratic approaches were dampened as a result. In contrast, personal freedom was attainable in North America at that time. The perspective that you could own land and start your own business was very attractive, for instance, to German immigrants. But North America had climate variations too.

Can your findings be transferred to the current climate discussion?

First and foremost, our findings stand for themselves in the historical and societal context in which we examined them. But we now understand much better how all the factors interacted. Similar to the 19th century, simple explanatory models don’t apply to today’s climate discussion. We are dealing with a lot of factors that interact in a complex fashion. Take Syria, for example: It goes back to the Arab spring, which came from the rising price of bread and food supply shortages. Droughts in 2010 and 2011 led to a worldwide shortage of wheat and rising prices in Egypt. The frustration, along with other reasons, expressed itself in the Arab spring. And then came this unspeakable cascade of events, which ultimately led to civil war and all the upheaval in the Middle East.

Einfache Erklärungsmuster greifen in der heutigen Klimadiskussion nicht, sagt Rüdiger Glaser. Foto: Thomas Kunz

Will there be climate refugees in the future, then?

Climate change affects food security, water availability and, ultimately, human health, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa. Add to it political instability, latent poverty and a general lack of perspective, a lot of people decide to leave. The pattern often begins with urban migration from rural areas, but then they move away from the country altogether to other parts of the world that promise security, a perspective and wealth. Just as North America represented the headwaters for 19th century Europe, today it is Europe that is the target region in which so many refugees are placing their hope.

What is the solution?

We have a global responsibility. We should combat the reasons for emigration in the first place. Prerequisites include a North-South dialogue, stronger development work, food security, health, participation and education along with political and economic stability. In other words, people need the prospect for a good future. We have known this for years, but the recent wave of refugees points to the current urgency for these approaches. A lot of people have long forgotten the heat wave that hit us in the so-called summer of the century in 2003. In that year 50,000 people died in Europe due to the climate. We need to remember that we are not invincible.