Movement!

Freiburg, Sep 06, 2018

Events such as the "Paris May," protests against the Vietnam War, and the shooting of Rudi Dutschke made headlines in 1968. The year is considered the high-point of the student revolts that changed the world in the 1960s and 1970s. But how did the developments unfold? And how deeply did they alter society? Fifty years later, opinions differ. Mathias Heybrock asked University of Freiburg researchers to summarize the impact of the student revolutionaries of 1968. He has produced a mosaic of thought from a range of disciplines.

Many of the students who protested in 1968 went into teaching later on, taking new instructional concepts into the classroom with them. Illustration: Svenja Kirsch

Throwing tomatoes and women's councils

When 1968 is mentioned, the "generation gap" is the first thing that comes to mind. Young Germans distanced themselves from their parents, whose lives had been dominated by fascism, and tried to throw off the imposed structures of a rigid, post-war society. "That's right for the most part," says Prof. Dr. Nina Degele, a sociologist. She continues, "But what's at least as important is the change in the relationship between the sexes. That's when the famous tomato throwing incident comes to light."

Back in the 1960s, gender roles were still very traditional, even among the students. "You weren't just together. You were married," says Degele. Keeping house and raising children remained the province of women, she explains. Of course there were women members of the Socialist German Student Union ("Sozialistischen Deutschen Studentenbund - SDS"), which played a dominant role in the protests in 1968. "But they often remained in the background and were allowed to do things like serve coffee and distribute leaflets," Degele continues. As the sociologist puts it, that was the case until Helke Sander, a delegate of the Action Committee for the Liberation of Women ("Aktionsrat zur Befreiung der Frauen") gave a speech at an SDS conference in September 1968 in Frankfurt about the "Revolution's Cleaning Women." When another SDS member, Hans-Jürgen Krahl, moved to take up the day's agenda without allowing so much as an opportunity to discuss the speech, another woman student, Sigrid Rüger, pelted him with tomatoes. "That set a whole lot of things in motion," emphasizes Degele. The women went on to form what were known as "women's councils," set up day-care centers for children, and opened their own women's book stores, where men were forbidden entry. The next milestone came in 1971, when the women fought for the right to control their own bodies and reproduction. They took to the streets against Paragraph 218, the law that made abortion illegal in Germany. Says Degele, "Alice Schwarzer published the cover story, 'We've had abortions!' in the news magazine 'Stern.' That was really important."

"Penis-Power is Limited" could be read on posters during demonstrations back then. Regele states, "For many men, that was really major and quite shocking." The sociologist says she understands that completely: "They were so focused on the societal level. Thinking that the personal could be political was way too much for them." They only grudgingly began to reconsider their own gender roles and the relationship between the sexes, but what matters is that they started, she explains. The women's movement nevertheless had a lasting effect. "That commissioners for gender equality are employed today in town halls and Gender Studies is offered at universities, those are all clearly effects of the women's movement," she says.

Comedies were popular, while crowds avoided politically critical films. Box office figures reflect audience preferences. Photo: Krists Luhaers/Unsplash

Molotov cocktails on the movie screen

When Prof. Dr. Robin Curtis talks about 1968, one of the first things she considers is the box office. That year in Germany, the American cartoon film "The Jungle Book" topped the ratings. Next, came the German comedy, "Zur Sache, Schätzchen," and the sex education documentary, "Das Wunder der Liebe" ("The Miracle of Love"), created by Oswalt Kolle. The director of the Department of Media Culture Studies finds two aspects of this interesting. The first is that people back then enjoyed watching German movies more than they do today. And second, that entertainment was dominant. Says Curtis, "There was also the feminist film, 'Neun Leben hat die Katze' ('The Cat Has Nine Lives')‚ or the later film 'Rote Sonne' (Red Sun). But people didn't flock to see movies that took up political issues." Still, even entertainment films and specific genres reflect the times in which they're created, says Curtis. The snazzy comedy "Zur Sache, Schätzchen" was one of the first to portray something other than a traditional middle class lifestyle. Meanwhile in the US, the science fiction film "Planet of the Apes" and the horror movie "Night of the Living Dead" made it into the top-ten in 1968. "Both of those had clear references to the black civil rights movement in them," stresses Curtis.

In West Germany, revolutionary films were primarily created at the "Deutsche Film- und Fernsehakademie-DFFB" (German Film and Television School-Berlin). "The training people received there was anti-hierarchical. Everyone learned everything, not just direction, but camerawork, editing, and audio. And back then no one was thinking about the commercial value of cinema," says Curtis. Among the students was Holger Meins, who directed the three-minute short film, "Wie baue ich einen Molotowcocktail?" ("How do I build a Molotov cocktail?"). Meins later went on to join the terrorist group the RAF ("Rote Armee Faktion"/Red Army Faction) in 1970. Curtis explains, "The idea was to be a radical filmmaker – something like Jean-Luc Godard. So someone whose radical making of films means they cease to be a filmmaker."

Curtis says that from today's perspective, it is important to avoid idealizing the student movement of 1968. She refers, for example, to the proportion of women who work in the film industry. "Of course there were women directors back then," she says. Among them were Ulla Stöckl and May Spils. "But their numbers have in no way increased since then. We shouldn't overestimate the power of that period to trigger change," she adds. Even genre films expressed a certain skepticism back then, she explains. In the "Night of the Living Dead," a black man is the only survivor of the attack of the undead. At the end of the film, he is shot and killed by police.

Protest doesn't always come from the left

The culture of protest is an integral part of society today. The historian Dr. Birgit Metzger. says, "It is very present and drives many discussions. But she notes that protest culture today is less dynamic than it was in the 1960s. "1968 was a signal for a process of change that unfolded over a longer time period," says Metzger. Back then, the students took to the streets first. Metzger specifies 2 June 1967 as a key date. That's the day that a police officer, Karl-Heinz Kurras, shot and killed 26-year-old Benno Ohnesorg during a demonstration in West Berlin. "That caused major mobilization, and radicalization as well," reports the researcher. She adds that the question arose about whether violence could be a legitimate means of protest. But only a minority supported the path of politically-motivated assassination taken by what would later become the RAF. By contrast, middle class society back then perceived as violent forms of protest that seem harmless today and reacted sharply to them. Police, for example, used water cannon and truncheons to break up a sit-down strike in Hamburg in 1966.

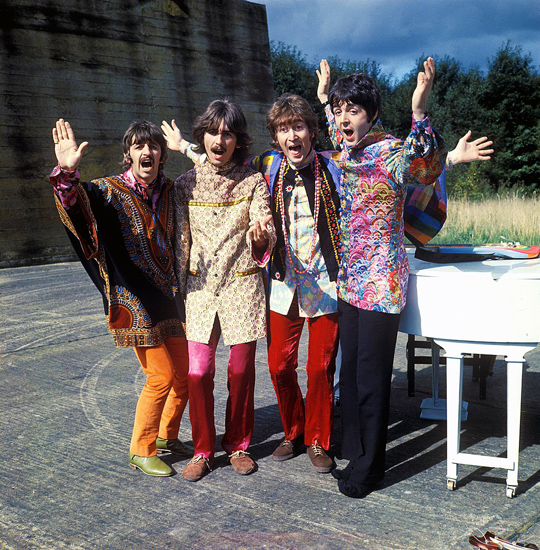

Psychedelic concerts: The film score of the movie "Magical Mystery Tour" put the Beatles at the top of the British and US charts in the late 1960s. Photo: Parlophone Music Sweden/Wikimedia Commons

According to Metzger, there are three characteristics of the culture of protest. There is, first of all, the rational side, which is shown during a political demonstration. It features posters and slogans that formulate demands and positions. Beyond that, there is a playful, creative component. Metzger explains, "Today you can see it in flash mobs that suddenly burst into people's daily routine and use clever presentations to move people to think and observe. And third of all, says Metzger, the overlap between protests and alternative life styles is basic. "You don't just protest, you do things. You create your own alternative world to live in," she adds, naming the day-care centers and social movements of the 1970s as examples.

These days, Metzger describes protests as being heterogeneous and diversified, in part through opportunities created by new media: "And they're by-and-large not automatically, liberal-leftist, anti-authoritarian movements. They can also be conservative or from the extreme right. That changed about fifteen years ago." The historian looks back on the rightist movement, the "Autonome Nationalisten" (Autonomous Nationalists), who at the time adopted the chaotic organizational approach and hooded sweatshirts of their leftist counterparts in order to appeal to young people who approved of the political tenets of the NPD (The National Democratic Party of Germany) but found their appearance rather unappealing.

Bands stepped onto a global stage

So what music characterizes the revolutionaries of 1968? "That started much earlier," says Dr. Knut Holtsträter of the Center for Popular Culture and Music (ZPKM). He says that 1964 was a significant year. That was the time of the "British Invasion," when the Beatles and Rolling Stones were taking hit parades in the US by storm as their fans followed in screaming ecstasy and made the clamor generated by Elvis Presley seem like someone with lumbago. "And then it just exploded in no time at all," summarizes the music scholar. The band the "Grateful Dead" was founded in 1965. Two years later, Jimi Hendrix's debut album "Are You Experienced" was released. Finally, in 1968, the hippie movement reached a climax in the "Summer of Love," and there were countless bands, says Holtsträter. The music they produced was psychedelic and allowed for intoxication and other altered physical states. "That was new. It hadn't happened before. And entire crowds of young people could see themselves reflected in it," says the music researcher, pointing out that music hadn't been as political earlier. "Before that, the songs in the charts were about private things. It would've been outrageous for someone to take up a position against war or discrimination against blacks or women," he adds.

Music reflected the attitude towards life of the generation of 1968. It also had a very solid impact on society. "The new musical style changed the market for music," says Holtsträter, Until then, the single had been dominant. Now, the LP – with songs on it that were far longer – became more widespread. The first concept albums came out that featured not only a single hit, but the artist's entire work. Nevertheless, says Holtsträter, you still couldn't really speak of a counter culture at that time, because these records were being marketed by the giants of the recording industry. They promised good business and were sold often and everywhere. In Germany, too, where they were listening to the same music as in the US, with a few national peculiarities. "Here, bands like Amon Düül developed "Krautrock," which were to gain an international audience later on," he explains.

"Respect All Women:" A protest group uses banners to express their demands and positions. Photo: T. Chick Mcclure/Unsplash

So what remains? "The politicization of popular music, of course," says the researcher. But even more significant for Holtsträter is perhaps the establishing of the first bands: "Before, music was always hierarchical, the orchestra had a director, and individual performers hired accompanists as employees. Then along came the band and suddenly there was a collective, in which every member was important." He adds that pecking orders established themselves in these groups as well, "But it was still a newer and more carefree form of organization which is a constituent feature of music today."

Bringing history into the classroom

Prof. Dr. Sylvia Paletschek stands up and brings a book over to the desk. The textbook for elementary school history classes is called "Entdecken und verstehen" (Discover and Understand). "It was written by Thomas Berger von der Heide," says the historian. He was a student in Freiburg in 1968 and a member of the university's constitutional assembly that was to take part in writing a new "constitution" for the university. When the country was debating educational reform in 1968, Freiburg was already an important center. Then in 1965, a national movement called "Aktion Bildungsnotstand" (Operation Educational Emergency) was organized from here. The educator Georg Picht, who was then the director of the private school Birklehof bei Hinterzarten, had already published his essay "Die deutsche Bildungskatastrophe" (The German Educational Disaster), which made a big impact. Says Prof. Dr. Ulrich Bröckling, a sociologist, "That made it apparent that the students weren't the only ones who were dissatisfied with educational policy." Government authorities also saw a massive need for change due to the sharply rising numbers of students. But how should the reform look? And how much say could students have in it? "During the protests in 1968, those questions became matters of open dispute," says Bröckling.

The full professors viewed the intervention as a threat to freedom of research and teaching. They didn't want to bend to the pressure being placed on them by the students, and their demands to be allowed a say. Another reform position, called "Drittelparität" (Third Parity) supported a balanced composition of university committees among professors, mid-level faculty, and students. This policy was backed by not only the radical SDS, but also the conservative "Ring Christlich-Demokratischer Studenten - RCDS," (Association of Christian Democratic Students). The atmosphere was highly charged, even hostile. Says Paletschek, "The heated debates nevertheless left people feeling, 'I'm able to influence and initiate a transformation process."

Many of the students who protested back then went on to become teachers. At their schools, they introduced new instructional concepts and content that they had tried and tested first at their universities after 1968. "Some of these teachers even created textbooks," says Paletschek – like Thomas Berger von der Heide. She summarizes, saying that these educators had shaped history and new methods for teaching the subject as well.