At your service

Freiburg, May 30, 2017

The Freiburg historian Dr. Andrea Althaus has explored the reasons behind the large number of young women who migrated to Switzerland throughout the course of the 20th century. Because there were not enough maids and service personnel in private households and hotels, around 30,000 female immigrants worked in the Swiss Confederacy between 1920 and 1960. Why did so many jump at the opportunity?

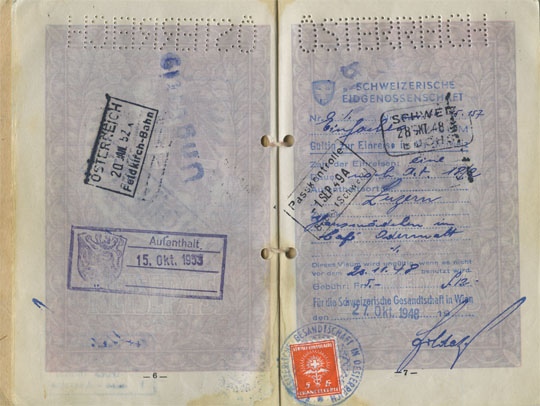

Idyllic landscapes, high wages and great food: Switzerland lures many young women during the course of the 20th century, such as the hotel worker Hilde Grangl in 1952.

Photo: Hilde Grangl

Great food, high wages, idyllic landscapes and cities completely spared by the ravages of two World Wars: Switzerland lured many young German and Austrian women throughout the course of the 20th century. However, it wasn't just the heavenly idea of delicious meals and tons of money that moved these women to emigrate. It was often their only chance to escape a strict parental household or dissatisfying factory work. It was a chance to learn something new.

Independent and free at last: For many of the women their time in Switzerland was a time for growing up.

Independent and free at last: For many of the women their time in Switzerland was a time for growing up.

Photo: Christa Strack

"We just wanted to get out of there," is something Andrea Althaus heard a lot during her conversations with some of these women. The majority of them were between 18 and 25 years old when they migrated to Switzerland. In her dissertation based on 79 life stories she gathered either in an interview or in written form, the historian refutes the common notion that the women were victimized as "maids" and immigrants. "The women have fond memories of their time in Switzerland. A lot of them said it was the best time of their lives," reports the historian. Maja Pichler is one of them. The Austrian worked as a hotel worker in Switzerland from 1957 to 1964. "It was heaven for me," she says.

Private households and the hospitality industry

Private households and the hospitality industry were the center point of her analysis. Depending on where they worked, the women's daily routine varied considerably. „Working conditions in the seasonal hotel business were particularly miserable. They had a legal right to a day off, but during the peak season that was mostly ignored," says Althaus. The workload in private households was rather heavy, but they typically got two free afternoons off as the law dictates. "Especially the women who grew up in a rural setting had a most positive memory of their brief leisure time," the researcher emphasizes. On the family farm, they always had to help out – for the first time in their lives they got to manage their own time as domestic workers in Switzerland.

How they perceived their free time is a great example for the biographical dimension of migration. For Althaus „"migration" means more than just the geographical journey from A to B. "Even childhood experiences shaped the way they experienced their time in Switzerland. Changing addresses had an effect on how the migrants saw themselves and the world. It changed their biographical perspectives."

The worker shortage in Switzerland created favorable conditions for the migration flow that solidified into a migration system over the years due to personal networks. A lot of women who were already in Switzerland asked their friends to join them. According to Althaus the personal contacts explain why German women continued to migrate well into the 1960s despite the "Wirtschaftswunder" (economic miracle) at home.

The majority of women returned home after several years to settle down and get married. For others, however, Switzerland was just the first stop in their migration. Many went on to England or the US thereafter.

Attack on Swiss sovereignty?

While the young German and Austrian women did not create the foreign infiltration discourse, they certainly shaped part of it. In the first half of the 20th century, it had an anti-German tone. "The Swiss were gravely concerned about foreign infiltration. Du to their origin, gender and professional activity, they saw German 'maids' as a foreign infiltration threat," explains Althaus. As domestic workers and potential wives to Swiss men, they were accused of spreading foreign – that is, monarchical or Nazi – ideology as well as infectious diseases to families. They were afraid Swiss sovereignty could be weakened from the inside out. The discourse became a political issue, which later led to a more restrictive immigration policy.

The shortage of household and hotel personnel was so grave that many young German and Austrian women were allowed to migrate to Switzerland. Personal networks amongst the women quickly arose, leading to a greater willingness to emigrate well into the 1960s.

The shortage of household and hotel personnel was so grave that many young German and Austrian women were allowed to migrate to Switzerland. Personal networks amongst the women quickly arose, leading to a greater willingness to emigrate well into the 1960s.

Photo: Margarete Simhofer

The women reported that they were often poorly treated and viewed as „foreigners" during that time. But most of the verbal attacks came from outside the families where they worked. The families themselves showed a great deal of support. Swiss female bosses played a particularly important role. Some of the immigrants said their female boss was like a second mother to them as they learned a great deal from her. "One woman said she learned how to assert herself through her boss' example," says the historian.

Did the women find happiness in Switzerland? Andrea Althaus agrees. "From an emancipatory perspective they certainly did. But you have to consider that oral life stories are almost always presented as success stories."

Judith Burggrabe

Exhibit

The exhibit „Mädchen, geh' in die Schweiz und mach dein Glück" („"Girl, go to Switzerland and find happiness") in the Dreiländermuseum Lörrach will run until October 1, 2017 and shows the results of Andreas Althaus' study.