A Piece of the "Russian" Mosaic in Freiburg

Freiburg, Jul 20, 2020

Unlike Baden-Baden or Berlin, Freiburg has up to now not really been perceived as having a "Russian" past. University of Freiburg Professor of Slavic Philology and Gender Studies, Elisabeth Cheauré, has changed that with her brilliant, information-packed, illustrated book "Das 'russische' Freiburg: Menschen – Orte – Spuren" ('Russian' Freiburg: People – Places – Traces). The volume reads wonderfully and moves readers to take a 'Russian' tour of the city. Jürgen Reuß speaks with Elisabeth Cheauré about her unexpected research findings, the people who maintained the links between Freiburg and Russia, and how to cope with the brevity of cultural memory.

Artist Igor Ponosov disguised both symbols of the University of Freiburg in white and placed them in a cardboard house during the Russian Culture Days in 2017. Photo: Klaus Polkowski

Artist Igor Ponosov disguised both symbols of the University of Freiburg in white and placed them in a cardboard house during the Russian Culture Days in 2017. Photo: Klaus Polkowski

Ms. Cheauré, "Russian" Freiburg is certainly a familiar topic for you as a Slavic Studies specialist. When you were researching your book, did you nevertheless make surprising discoveries?

Elisabeth Cheauré: There was and is far more "Russian" life in Freiburg than I'd previously suspected. I said farewell to the initial idea that I could quickly handle the topic in a short brochure. In conjunction with this, I rapidly noticed how productive it is to limit yourself to a particular and clearly defined perspective – in order to make the concept of the "spatial turn" fruitful. Freiburg is a place that, with respect to Russia, isn't all that close, as it would be the case for Baden-Baden or Badenweiler for example, not to mention Berlin. That's why the discoveries were even more significant for my own subject, Slavic Studies.

Could you give us an example?

The importance of Ivan Zvetayev, the father of the world-famous author Marina Zvetayeva, comes to mind here. The knowledge up to now was that he hardly played a role in Freiburg. But he was here a number of times and made great efforts to acquire art from the Freiburg Minster for the museum he founded, which today is the Pushkin Museum in Moscow. We have him to thank for the stories of Freiburg, together with his two daughters, Marina and her sister Anastasia, who also wrote. A high point of this common history came in the 1990s, when the mayor of Freiburg at the time, Rolf Böhme presented the street sign for a "Marina-Zwetajewa-Allee" (Marina Zvetayeva Boulevard) in the Rieselfeld area of the city. That then became "Marina-Zwetajewa-Weg" (Marina Zvetajeva Way). And I didn't know all the aspects of the story of Maxim Gorki in Günterstal until now. He even wrote his own "Freiburger Notizen" ("Freiburg Notes") and there are photos of his time in Freiburg that I have been permitted to publish for the first time.

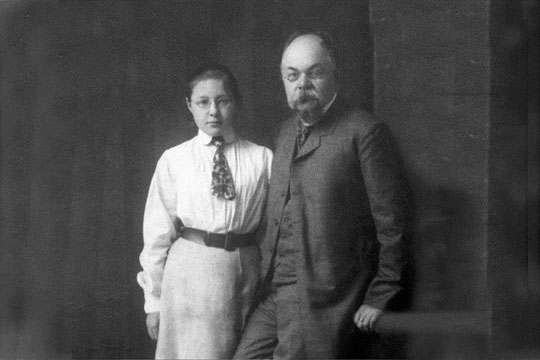

Ivan Zvetayev was a social scientist who was renowned in Europe. His daughter, Marina, later became a world-famous author. Marina and her sister Anastasia went to school in Freiburg in the beginning of the 20th century. Photo: Marina Zvetayeva Museum, Moscow

Ivan Zvetayev was a social scientist who was renowned in Europe. His daughter, Marina, later became a world-famous author. Marina and her sister Anastasia went to school in Freiburg in the beginning of the 20th century. Photo: Marina Zvetayeva Museum, Moscow

You're attaching the "Russian" history of Freiburg above all to individuals.

Yes, that's another of my book's insights. Structures are important for initiating and continuing transfer and contact between cultures. Yet individuals are an even more vital aspect of this, which is consistent with the results of culture transfer research. The best programs fail to achieve anything when the people aren't there who really do something.

And perhaps your most important sources of information were less the libraries than some of these individuals?

Yes. I owe many documents, images, and stories to direct contact with these actors. One of the book's aims is also to rescue these people's deeds from being forgotten, because some of them are still living, and with them, their most important memories. I was surprised about how many people there are in Freiburg who are committed to and have served to create an image of Russia that goes beyond the clichés. Yet in part, cultural memory is nevertheless very short.

What do you mean by that?

Who still remembers the first Russian Culture Days in 1989, the slogan of which was "Russisches Erbe – Sowjetische Gegenwart?" ("Russian Legacy – Soviet Present?") From my point of view, Freiburg experienced a number of unique things back then. Or the exciting ties between Russia and the Wallgraben Theater and Theater Marienbad? Or the activities of the "West-Ost-Gesellschaft" ("West-East Society") founded in Freiburg? When the Russian Culture Days were relaunched a few years ago, the memory of what had already taken place was apparently already lost – which, by the way, is a very normal process.

Elisabeth Cheauré is the head of the Zvetayeva Center, which among other things has set up a cultural offering on "Russian" Freiburg. Photo: Elisabeth Cheauré

Elisabeth Cheauré is the head of the Zvetayeva Center, which among other things has set up a cultural offering on "Russian" Freiburg. Photo: Elisabeth Cheauré

Beyond the diverse cultural and commercial contacts – has the understanding of Freiburg locals for what is "Russian" also been strongly influenced by the immigration of ethnic Germans from Russia, also known as "russlanddeutsche?"

What is "Russian" is a complex thing. Is a "russlanddeutsche" migrant family from Kazahkstan or Western Siberia typically "Russian?" The older generation of "russlanddeutsche" was in the Soviet Union and therefore socialized as Russian, but in their domestic identification documents there was often a note – "Nationality: German." Even the people of Jewish origin who came to Freiburg in the 1990s were often perceived here as "Russians" because of their language, while in the Soviet Union their identification documents mostly contained the note "Nationality: Jewish" – and this is important – the word was not meant to designate religion. Today there's no Soviet Union anymore. Their places of origin are now in new countries, such as Kazahkstan. That's why I insisted on putting the word "Russian" in quotation marks in the book's title. It was always a country of many peoples, whether it was tsarist, Soviet, or today's Russia.

The famous Dostoyevsky translator Svetlana Geier was also from Kiev, so the Ukraine. …

…she always said: "Russia is where I am." Consciously, I didn't want to make any ethnic, religious, or national simplifications about what "Russian" can be in my book. On the contrary, I wanted to raise awareness of this complex issue. That's why I above all used the criteria of regional origin and Russian as the language of communication, and last but not least, that these people were perceived as "Russian" in Freiburg. That's true, for example, of the many Jews who came to study in Freiburg at the beginning of the 20th Century because they were discriminated against in tsarist Russia.

There's a certain gap in your book between 1945 and 1989. Why?

Yes, there is a gap. The formation of blocs in the Cold War had a major effect on cultural exchange. There are very few individual actors who manage to break through this. I attempt a bit with the history of the Russian Orthodox community in Freiburg, the theater, or the Russian Chorus to make that comprehensible. But of course this book is just the start. Presumably there's a great deal more to discover.

And you're not alone in your quest …

No, I'm thinking primarily of the research of the international research training group, "Transfer of Culture and 'Cultural Identity.' German-Russian Contacts in a European Context" or projects being carried out by the special research area "Muße" (Otium). But still, without the support of the city, the academic society ‘Wissenschaftliche Gesellschaft Freiburg’, and the New University Endowment, it wouldn't have been possible to publish this book in this form, and with it, to provide a new piece of the mosaic that forms the history of the city and university. And don't forget, the fact that the Zvetayeva-Center has been established here in the meantime shows how alive "Russian" Freiburg is today.