Gone to Their Final Rest – At Last

Freiburg, Apr 25, 2019

At the Linden-Museum Stuttgart 12th April 2019 was dedicated to remembrance of and accountability to the Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders: their two flags – one black and red with a brilliant yellow sun in the center, the other blue, green and black with a white headdress – adorned caskets which held ten skulls of their ancestors. The federal state government presented the mortal remains to a delegation from Australia, mortal remains that were brought to Baden-Württemberg more than 100 years ago for the purposes of “racial research” – eight of them had been part of the Alexander Ecker Collection of the University of Freiburg.

In Queensland an indigenous Australian demonstrates the rituals of his culture. Photo: Rafael Ben-Ari/stock.adobe.com

“As the rector of this university I deeply regret what was once done under the guise of science,” said Prof. Dr. Hans-Jochen Schiewer at the presentation. The graves of indigenous Australians were often ransacked and their bones sold to researchers from Europe. Schiewer appealed for a wholehearted investigation of colonial crimes. “There is no room for excuses here. We must use every means at our disposal to determine the origin of mortal remains and return them to their homelands.” The skulls and bones are of special ritual significance to the indigenous communities: only once they have been buried in their home soil can the spirits of the dead return.

Back in 2014 the University of Freiburg presented fourteen skulls of members of the Herero and Nama ethnic groups to the government of Namibia. The bones had found their way into the collection from what was once German South-West Africa during the colonial era. Discovering the sources, Schiewer said, would be an arduous process, but reappraisal of Freiburg’s historic collection has been underway for more than a decade and is yielding successes. “By repatriations we are also creating a new culture of remembrance, and areas of unintentional marginalization, ignorance or the desire not to know are becoming ever smaller.”

More than 150 years ago, however, Alexander Ecker had something else in mind. The Professor of Zoology, Physiology and Anatomy at the University of Freiburg was studying the core issues of life. He wanted to understand how people and animals develop, what strengthens an organism and what makes it weaker. In 1860 he established an anthropological collection which consisted not only of human skulls and skeletons from the region around Freiburg, but also from Africa, Australia and Asia. Ecker had first-class contacts with researchers who were for example conducting archaeological digs in colonial regions, but also with dealers and collectors. Ecker’s successors who curated the collection after his death in 1887 followed in his footsteps. The collection grew from decade to decade to nearly 1,400 skulls.

In 2014 the University of Freiburg held a solemn ceremony to present fourteen skulls to a delegation from Namibia. Photo: Baschi Bender

Ideologically biased

What today sounds like a cabinet of horrors was the apex of research in the late 19th and early 20th centuries: eugenics was an up-and-coming young science that promised to improve mankind. The man who named it, British natural scientist Francis Galton, worked on an alluringly simple genetic assumption: that it was right to increase the share of positive genetic material and minimize the less desirable parts. Yet as so often occurs in the history of science, the facts were not so clear and simple, but the distorted result of an ideological obfuscation. Galton was convinced that “good breeding” prohibited the “interbreeding of races”. The “lower races” were primarily those with darker skins, whereas he regarded whites as the ideal.

And so the path was laid to “race hygiene” and its politicization – and was perfected in Freiburg: at the start of the 20th century, Eugen Fischer took on Ecker’s collection, and until he moved to Berlin at the end of the 1920s resolutely expanded it with “human materials”. Fischer associated certain physical features with alleged character traits. The doctor’s work became a key pillar of the Nazi’s race laws, and Fischer became their greatest advocate in research. So Schiewer believes that the University of Freiburg is beholden to tackle its own history in this field and reappraise it.

Air raids destroyed collection

After the Second World War scientists turned away from the racial ideology, and were drawn into other paths by new approaches and methods – and the Alexander Ecker Collection was increasingly forgotten. Eventually, Freiburg historian Prof. Dr. Dieter Speck realized the fact that the holdings contained ethically problematic exhibits, “When the collection came to us in the university archive in 2000, I put a ban on research work with them and started to find out about them item by item.”

But the collection was a muddled hotchpotch, the documents were more confusing than helpful, “There was never a systematic catalogue. Many items were destroyed in air raids in the two world wars. In some cases the curators replaced items but didn’t make a note of this. And in addition the collection often moved house, leading to labels getting mixed up,” explains the head of the university archive. However these setbacks could not be allowed to stop the University of Freiburg fulfilling its ethical and political responsibilities: in 2004 the rectorate passed the resolution to study the bones to identify their origin and repatriate them to the relevant countries, that is, to restore the mortal remains to their home.

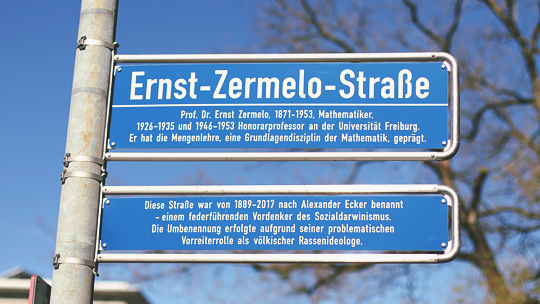

No credit where no credit is due: once named after Alexander Ecker, since 2018 the Eckerstraße has been called Ernst-Zermelo-Straße. Photo: Sandra Meyndt

Investigating the clutter

Speck shared the detective work with Prof. Dr. Ursula Wittwer-Backofen, head of Biological Anthropology at the University of Freiburg. She specializes in researching the forensic analysis of skulls. Almost ten years ago she started to study items from the Ecker collection – so far Wittwer-Backofen has tested almost fifty skulls using various methods. These include, for instance, examination under UV light which enables reading lettering that was once on the skulls, and analysis of DNA and isotopes.

This method uses certain chemical elements that are stored in the bones to find clues to their origin. “Over the course of our lives, traces of our environment are deposited in our bodies – whether they are traces of drinking water or a certain diet,” explains Wittwer-Backofen. “We can never be 100 per cent certain, but with a combination of methods we have sufficient evidence to allocate a geographic origin to an exhibit.”

Collective reappraisal

“We’ve undertaken pioneering work with this research in the past ten years,” says Schiewer. “No one has gained as much expertise in this field in Baden-Württemberg as we have.” Now it is time to make use of this knowledge. The federal state government wants to examine systematically historic collections that are held in its museums, universities and university hospitals. The University of Freiburg will also continue to examine its historic collection – Speck and Wittwer-Backofen believe that about two-thirds of the holdings come from Europe and are morally acceptable.

The ongoing work will take many more years, Speck asserts, “It’s a never-ending story. But that’s normal for such collections.” Ongoing investigations will also involve the relevant countries, Schiewer emphasizes, “We are shortly expecting experts from Australia with whom we can take the next few steps in reappraisal.”

Rimma Gerenstein