Who ya gonna call?

Freiburg, Mar 12, 2021

Fifty-one years ago Prof. Dr. Hans Bender founded the Freiburg Institute for Frontier Areas of Psychology and Mental Health (IGPP). This private institution studies what are called paranormal phenomena, such as ghosts, clairvoyance and telepathy. At the same time, Bender taught as a professor at the University of Freiburg. In the 1970s Bender, who died 30 years ago, also evolved into a media star, known from the television and widely-read newspapers throughout West Germany. Freiburg historian Dr. Anna Lux has researched the history of parapsychology and its most famous exponent. Anita Rüffer spoke to her about her recently-published book, in which Lux outlines the debates concerning the boundaries of science and pseudoscience and explains how the highly-controversial subject of parapsychology was able to gain legitimacy in public – and lost it again.

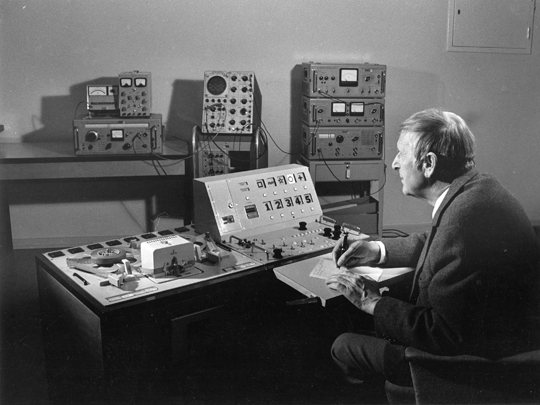

The 'Psi-Recorder 70' was developed for Hans Bender to use to study extrasensory phenomena scientifically. Photo: Leif Geiges/Institute for Frontier Areas of Psychology and Mental Health (IGPP)

Ms Lux, parapsychology researches phenomena such as apparitions, prophetic dreams and telepathy. Why did you want to engage with things whose existence is disputed by many?

Anna Lux: Parapsychology is a fringe discipline, and that’s exactly what drew me: researching scientific history from the outside in, instead of within established subjects. I have no reservations or issues with regard to parapsychology.

You’ve commuted between your home in Leipzig and Freiburg for some years now. Have you found a difference between the two cities with regard to parapsychology?

Very significant ones, in fact. Obviously, Leipzig is in the east of the country, the former GDR, and this was one of the most secular countries in the world, where they also fought against anything occult. When I came to Freiburg I was astonished at the broad-based popular interest in Hans Bender and parapsychology. On a course, we worked with students on the occult in Freiburg city history and created a guided tour on it. Around 100 people were interested and attended. It’s exciting to learn how this dichotomy can arise between an academic basis for the subject at the university and its broad effect.

Could it be said that the scientific roots of parapsychology are in Freiburg because of Hans Bender?

Bender didn’t start from scratch. Scientific investigation of the subject had already started in the late 19th century in the UK, where Spiritualism was very popular. At the Duke University in North Carolina, USA, in the 1930s, they experimented with quantitative statistical methods that yielded results which were regarded as remarkable. This gave it a boost as a legitimate field of research and was also a crucial contribution to Bender being able to found his private institution in Freiburg in 1950.

“What was distinctively modern and innovative about Hans Bender was that he wasn’t afraid of using what were seen as ‘shallow’ media,” says Anna Lux about the parapsychologist’s strong media presence. Photo: Jürgen Gocke

He even managed to establish parapsychology at the University of Freiburg. In 1954 a Chair of Frontier Areas of Psychology was set up, and a few years later it had its own department as part of the Institute of Psychology. What did this mean for the subject?

Hans Bender wasn’t an outsider, he was a recognized scientist with every academic honor and a very good networker. He was interested in explaining issues of parapsychology scientifically, rather than labeling them as ‘just’ religious or dismissing them in advance as a disease, delusion or deception. He held them to be the result of psychic abilities. He wanted to allow them space to be taken seriously. From his point of view, the university was this space. He hoped this would free the phenomena of taboos – as well as freeing those people who had had such experiences. You couldn’t simply dismiss them. Establishing parapsychology at the university meant that structures were developed, knowledge was recorded and funding could be secured. Bender was a brilliant academic organizer. And that was attractive to the university too. Parapsychology wasn’t taught anywhere else and therefore offered a USP.

Hans Bender was also very high-profile in the media. What exactly did he do?

He sought publicity via the mass media. For instance he gave a series of interviews to the ‘Bild’ tabloid newspaper. Magazines sent requests. In the 1950s Bender appeared on the still-new medium of television. On the radio there were advice programs. So he absolutely didn’t simply give dry academic lectures, rather, he sought a dialog with the general public, who were very interested in such topics, and he called on them to contribute their experiences. He wanted to use them as research material.

Rosenheim, Bavaria, 1967: Hans Bender visited people who reported paranormal experiences. The photo shows a woman looking at a ceiling light that she claimed would start to swing of its own accord. Photo: Leif Geiges/Institute for Frontier Areas of Psychology and Mental Health (IGPP)

So was Bender a kind of pioneer in science communication?

There were ways of popularizing science as far back as the 19th century. What was distinctively modern and innovative about Hans Bender was that he wasn’t afraid of using what were seen as ‘shallow’ media to raise the profile of his subject and reach a lot of people. And he was very effective in adapting to each medium.

The Chair of Frontier Areas of Psychology ceased to exist at the University of Freiburg from 1998. Did Hans Bender’s career finally come to a dead end?

I’d prefer to call it a hiatus. But yes: his goal of establishing parapsychology at the university can be seen as having failed in this form. The history of parapsychology is always also a history of its controversies. In the mid-1970s, critical and skeptical voices gained in influence. An important part was played by the famous spoon-bender and magician Uri Geller, who also drew a lot of controversy in parapsychology. Then there were fraud-related scandals in the field. Scientists and institutions and the mainstream media increasingly distanced themselves from parapsychology. The appearance of ‘New Age’ ideas with similar themes that were however interpreted quite differently increased the conflict. So parapsychology suffered a loss of legitimacy and credibility.

What’s left?

The IGPP private research institute still exists and is now one of the largest of its kind in the world, not least because of its impressive specialist library. There are still links with the university. The status of parapsychology as a fringe science remains as does the massive interest in its topics.