A Model for the Arab World

Freiburg, Dec 05, 2018

The revolution in Iran in the 1970s was unique in the Arab world. Although there has already been plenty of academic study of protest within that country, little is known about its influence on other Muslim countries. On research trips to Lebanon and Tunisia, the Islamic Studies researcher Dr. Simon Wolfgang Fuchs has looked for evidence relating to that time.

A symbolic figure, even after many years: with photos of the late leader of the revolution, the Ayatollah Khomeini (right), and his successor Ali Khamenei (left), this demonstrator in 2008 declares his allegiance to Iran as an Islamic State on the 29th anniversary of the revolution in Tehran, and that he is committed to fighting those that betray it. Photo: Simon Wolfgang Fuchs

In 1979, a combination of religious and political groups forced the last Shah to flee Iran, and changed the country into a republic. Although there has already been plenty of academic study of the revolution within Iran, little is known about its influence on other Muslim countries. “Iran was one of the most stable and powerful countries in the region. No one anticipated such a change could happen within just a few months. I’m interested in the major signal it sent to many other groups in the region,” explains Islamic Studies researcher Dr. Simon Wolfgang Fuchs of the Oriental Seminar of the University of Freiburg. He is researching how the Muslim world perceived, discussed, and was inspired by the revolution.

So Fuchs has been talking with activists and eye-witnesses locally, and combing through archives for sources from the time. “Since the points of view of many people have changed in the interim, my primary sources are periodicals and newspapers from various groups,” he explains. He uses these to trace the progress of the debate at that time. Fuchs began his research, which is funded by the Gerda Henkel Foundation as part of the “Islam, the Modern Nation State and Transnational Movements” special program, this year in Lebanon and Tunisia – in spring 2019 he will be traveling to Pakistan, India and Afghanistan.

Researching in uncertain times

“Because of the charged climate between Sunnis and Shiites, even I wasn’t sure how research locally would go – particularly with non-Shiite participants,” recounts Fuchs. “But so far I’ve only had positive experiences.” One eye-witness from Tunis, for example, packed his collection of documents in a box and let Fuchs take them to a cafe. “Without ever having met me before or knowing who I am. This trust encouraged me. It shows that there is an interest in this history being told and in someone dealing with this period.”

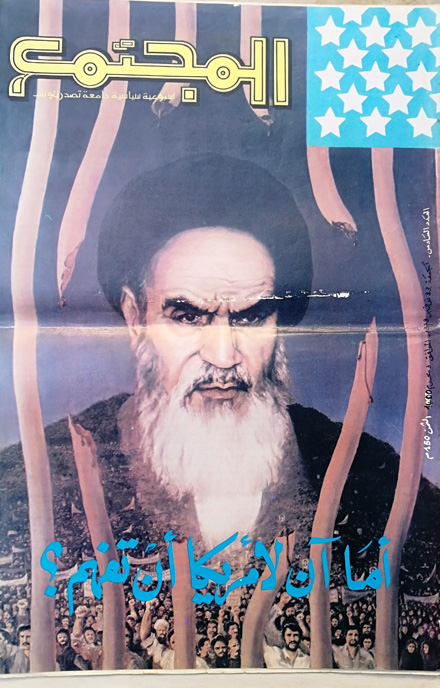

Simon Wolfgang Fuchs combs through archives for contemporary journals such as this one, which was published in Tunisia in 1979. Photo: Simon Wolfgang Fuchs

The reactions to the revolution began in autumn 1978 and exploded in the spring of 1979 when it became clear that something entirely new might arise in Iran. People in the surrounding countries were fascinated by this success and in many places also worked to bring about a change of power. At the same time, the Iranian Revolution was far more than a purely Shiite event. “At first it is hard to believe, because now in the Middle East and in South Asia we mainly see interdenominational conflicts between Sunnis and Shiites,” says Fuchs.

Fight against worldwide capitalism

Yet the revolutionaries’ goal was not only that religion should play a greater part. They were also committed to the fight against worldwide capitalism and anti-imperialism against the USA and the Soviet Union. “For many in the opposition the idea arose: if the Iranians have done it, maybe we can too,” says Fuchs.

After the revolution, Maoist activists in the Middle East considered how they too could reach the masses, and concluded that they would have to make greater allowance for religion to do so. In Pakistan even Sunni groups were unable to withstand the fascination of Iran. They adopted the symbols of martyrdom and suffering, which until then had only adorned Shiite banners, and reinterpreted them to their own ends.

One eye-witness from Tunis packed his collection of documents in a box and let Simon Wolfgang Fuchs take them to a cafe.

This-worldly issues also made waves in Iran. Fuchs is looking here in particular at images of women, at political and economic concepts, and at how Sunni groups perceived developments. “I expect that political thought and social concepts also shift in this period,” he says. For example, in later years an Islamist magazine from Lebanon illustrated all articles on the role of women with pictures of veiled women working in public – alluding to Iran which had already achieved such goals.

Yet the enthusiasm did not remain for long everywhere, as can be seen from the example of Syria. Here, the Muslim Brotherhood opposed the regime and hoped for support from Iran. However, Iran attempted to maintain good relationships with the Syrian government. “When this became clear, the mood rapidly changed. I am especially interested in the point until which the fascination remained and when the positive image of the revolution changes again,” Fuchs relates. Of course, this varies from country to country, “In Lebanon and Tunisia it didn’t happen very fast. People there told me how this event had electrified them, and there is still great interest today.”

Sarah Schwarzkopf